The Last World Cup as we know It

17.07.18

That’s what Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman fears World Cup 2018 might prove to be

Illustration : Hugh Tisdale, co-founder Philosophy Football

Writing on the eve of Italia ’90 in the magazine Marxism Today Stan Hey had this gloomy prediction:

“ The global success of football has almost certainly sown the seeds for the game’s corruption. There is now a momentum which seems to be beyond control. Those of us who have retained an optimism for football’s capacity for survival and ability to re-invent itself are already checking our watches. It’s starting to feel like injury time.”

What seemed to prove Stan wrong were all those evenings with Gary Lineker as a nation watched football re-establish its popular appeal and never mind FIFA or those missed penalties in the semi-final defeat to West Germany either. 28 years later and an England team at last winning a World Cup penalty shoot out, reaching a World Cup semi for the first time since 1990, Harry Kane lifting the tournament Golden Boot award for top scorer, surely its scraping the limits of Left miserabilism to suggest Stan’s prediction is about to come horribly true? Afraid not, Russia 2018 might just prove to be as good as it gets.

As guardian of a global game one of the good things FIFA has done, yes really they do exist, is expand the frontiers of football. Of course they’re after markets rather than nurturing the worldwide culture of the sport but taking the World Cup to the USA in ’94, Japan and South Korea in 2002 and South Africa in 2010 were absolutely the right thing to do. And in the same regard Russia 2018 too, the first post-communist country to host the tournament. However each of these host nations had some kind of proven domestic football infrastructure and in addition they had all previously qualified for World Cups, not as hosts but in their own right. The Middle East was the next most obvious part of the planet to take the World Cup to, but not Qatar. Apart from the scandal of the lethally unsafe labour practices that underpin the building of the new stadia, the deaths of these construction workers reportedly number in the hundreds, this is a country that has never before qualified, or come very close. There’s no depth or breadth to football in the country. Football is a tool of Qatari soft-power diplomacy and that’s about it.

A Middle Eastern host, an Islamic host, yes but the most obvious candidate that ticks all the right boxes is so obviously Iran that it could not have ever have even been considered speaks volumes. Instead Qatar won the bid and then it was swiftly decided that because of the intense heat in the country during June-July the tournament would be switched to the autumn. Resistance to this can be a tad Eurocentric, after all the southern hemisphere nations play much of their football in their winter, our summer. But the reality is for the northern hemisphere what makes the World Cup so special is that is at the end of the season. A once every four years, with a Euro thrown in too in between, summer of footballing love. This is what more than almost anything else draws in the crowds way beyond the footballing diehards. November 2022 will disrupt all this, an early winter break from the promotion tussle and Champions League that will struggle for attention out of their huge shadow, a kind of after-show to what is so rooted in our sporting calendar, the season.

What has defied Stan Hey’s pessimism more than anything else is the way that popular consumption of a World Cup overwhelms its marketing and commercialisation. At home that’s the TV audience, not in the house but turning watching the games into a mass public spectacle. Whilst away from home the travelling fans magnify this even more. The latters requires a huge existing set-up of cheap hotels, airbnbs, campsites and the like. England’s support in Russia was relatively small – the interest will be much bigger next time - but the South Americans, Japanese, Mexicans however travelled in their tens of thousands. It’s them who turn the World Cup into a carnival outwith the control of either FIFA or the host nation authorities. It will be wonderful if such a thing happens in Qatar but if these facilities are lacking it won’t worsening still further the absence of our summertime festival back home.

Qatar threatens giving the World Cup’s gloriously revived popularity a knockback and things could get even worse at the 2026 tournament. What makes a tournament so special is the way the host nation defines it, often in the process defying the worst possible stereotypes. No, Russia hasn’t overnight become a worker’s paradise but neither is it the hell on earth that much of the media build-up presented it as. It was the Russian people, not Putin, who turned their country for the past four weeks at least into a place to savour not to fear. Not content with UEFA choosing to ignore the importance of a single host nation by spreading Euro 2020 over the entire continent FIFA has awarded World Cup 2026 to the joint bid of USA, Canada and Mexico undermining this crucial national identity of the tournament. A process both justified and amplified by the expansion of the competition to 48 nations. This will result in either dragging out the tournament longer than the current four weeks, meaningless group games when the group winners are already settled, tired legs and poor quality football thanks to shortened recovery time. Quite possibly World Cup 2026 will suffer from all three, which coupled with tis lack of a single defining host doesn’t bode well.

Of course hope must spring eternal but it’s not looking good and once the World Cup loses its huge and hard-won popularity then it may never recover. These forces which create such a wondrous sporting event on a global scale are both within and without the control of FIFA. But if it sacrifices that which it cannot govern, this global popular reach of football, to suit those within its control, FIFA’s organisational ends and commercial interests, then it will only have itself to blame.

The World Cup is the one truly global team sport event. It is the emotional investment in their team of an entire nation, multiplied 32 times across the planet which defines it. Thus, Russia 2018 revealed another seed to its eventual downfall. No South American team in the semis, when that happened in 2006 it was the first now with no South American winner since 2002 it is in danger of becoming a habit. No African team made it beyond the Group stages, just the one Asian team, Japan and they went out, if more than a little unluckily, straight away too. The globalisation of European football, with club teams stuffed full of imported South American and African talent doesn’t appear to be benefitting the teams of the countries where they’ve come from. Football’s version of colonialism, fuelled by neoliberal globalisation, that’s what it is beginning to look like with nobody in their right minds imagining FIFA will be much minded to do very much about it, their guardianship of the global game never being more important than the drive for profit. Sounds familiar?

Still at least for four glorious weeks it did at least look like, as the song goes, ‘football’s coming home’. Call me po-faced if you want but I have a problem with this particular notion. Don’t get me wrong I like a mindless football chant, especially one with a half-decent rhythm as much as the next fan. But England, home of football, coming to, what does that imply exactly? In World Cup terms we are anything but. England boycotted not only the first World Cup, but the next two as well. We finally decided to join in at Brazil 1950, promptly losing 1-0 to the USA in the Group Stage. And when we hosted the ’66 tournament the then FIFA President, Englishman Stanley Rous, thought it was acceptable that the entire continent of Africa merited one place. Unsurprisingly they told where he could stick that and refused to take part. If we insist on nominating football’s home there’s only serious candidate, France, the country who invented this most wonderful of tournaments, the clue after all is in the name of the trophy, Jules Rimet. But the point is that this tournament works because football’s home is everywhere, it belongs to every corner of the earth, the one truly global occasion in our lives.

It is the people, the fans and the players who make World Cups not one country nor FIFA’s either. And right now just like Pelé in 1958 and the following three tournament in Mbappé, un garçon des banlieues, France and the world has a player who epitomises that for the next few World Cups to come. Merci beaucoup,but handle with care.

Mark Perryman is co-founder of Philosophy Football, AKA ‘the sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’. Our Liberté Egalité Mbappé shirt is available from here.

A National Reality Check

14.07.18

With no England World Cup Final to look forward to this weekend Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman looks back in hope

Illustration : Hugh Tisdale

On the eve of World Cup 2010 a book with just about my least favourite title of all time, Why England Lose, was published. Never mind, it proved to be an excellent read though as anyone who can remember our last sixteen 1-4 thrashing at the hands of Germany the book didn’t exactly have a happy ending.

The book, now repackaged with a more sales-friendly title Soccernomics, regardless is a great read. The theory of England’s losses begins with what is now a fairly familiar recounting of England’s World Cup record which despite 2018’s glories remains at best quarter-finalists on the whole. We’ll have to go some in 2022 and beyond that to reverse that historic pattern. The points about recruiting from a narrow base of the population have moved on quite a bit too, with an admirably diverse squad. Cue the hurt shrieks of the ‘political correctness gone mad’ brigade. No, its just that if you want to succeed draw on the widest possible talent pool, are we doing enough to talent-spot youngsters starting out in the game from the sizeable Asian, Chinese and East European migrant communities? That’s the question youth football coaches and scouts should be asking themselves. The authors of the book, Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski, make an additional point however about our talent pool. Why do almost all England players come from a working class family background. In 2010 the only England player from a middle class family they found was Peter Crouch, his dad a creative director at an international advertising agency. My alternative view would be that this remains football’s enduring appeal, despite the gentrification of how it is consumed and marketed the players are working-class connecting it at least in part to its roots as the people’s game.

The main part of their thesis however was explaining World Cup success in terms of the victorious nation’s size of population and ratio of registered professional players to the that overall total (thus ruling out the likes of USA, China and India). England’ top eight status but not perennial semis, finalists or winners therefore seems about right. And in quasi-Marxist terms this amounts to an admirably materialist, if for England fans depressing, analysis. But what about Croatia, population 4.2 million, Belgium, 11.4 million. Croatia will be the smallest nation in a World Cup Final since Uruguay’s successes in 1950 and 1930, and bear in mind the World Cup was a very different competition back then too.

During the course of this tournament Simon updated his analysis to prove an additional explanation for the apparent Belgian anomaly:

“ Most of today’s Devils (the nickname for the teams is The Red Devils) have been globalised since their teens when the emigrated to learn football in nearby countries. The are multilingual and largely above the Flemish-Walloon divide.”

A multicultural team not afraid either of being cosmopolitan about where it both learns and plays its football. Something similar can be said of Croatia. Far more mono-cultural than Belgium’s squad they are nevertheless smart enough to recruit from players whose families became refugees from the Balkans war but who’s sons want to play for their homeland. Croatian international Ivan Rakitic who grew up in Switzerland being perhaps the most obvious example. But Croatia’s starting eleven also included homegrown players who now turn out for the top European teams, Real Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan. And Liverpool.

Again it’s a materialist analysis that makes a lot of sense. English players who stick at home, in a top division that confuses being the richest league in the world with being the best, lack that dimension, pitting themselves against different styles, subjecting themselves to coaching and management approaches they might otherwise not experience, learning to live in another country, picking up a foreign langue, or three. Too many foreign players and managers over here? Until our England internationals choose to leave the comforts of home thanks to them its the closest thing we have to the globalised footballing cultures other nations benefit from.

That’s the materialism accounted for. We could add the good fortune of the almost entire absence of injuries and suspensions. England have never been so lucky on both fronts before but lets be generous and put that down to good planning, better sports science than previously and an improved disciplinary record.

It is the other key factor that is much harder to root in any version of materialism. The luck of the draw. Every single time before England finishing second in their group condemned them to a really tough quarter-final and in some cases almost as tough an opponent to beat at the last sixteen stage too. In Russia after finishing second in their group the combined might of former winners Brazil, Argentina, France, Spain and Uruguay plus reigning European Champions Portugal were all in the other half of the draw and couldn’t be played until the Final. When we faced teams in our half with half-decent rankings, Colombia and Croatia, we either failed to beat them over 120 minutes or lost. It is hard to imagine England will face such a fortunate draw for a long time to come. And if Germany, Italy and the Netherlands get halfway close to restoring themselves to former glories the task becomes that much harder again.

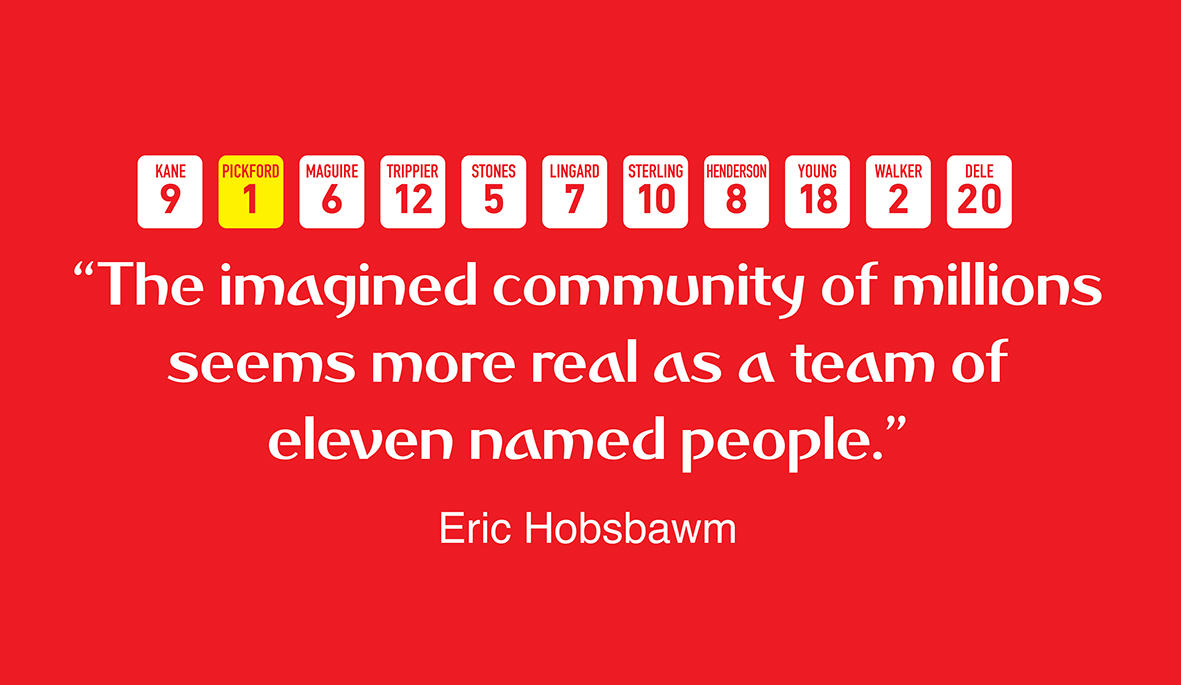

Is this a case therefore of just enjoying England while it lasts. No, not all. A young squad, a manager with a sense of purpose, together with the fans this summer we’ve all written our own history. Always looking backwards, to ’66 and ’90 not forwards, more than a bit laid to rest. If we’re looking for a 2018 legacy this surely is the one to build on, one we can affect. No more looking nostalgic as our national comfort blanket, one that is invariably, and uncomfortably, confused with an imperial, a martial, and racialised history. The past after all is a different country. Instead for the last four and a bit weeks we’ve had eleven named people and their best, with us chering them on, to provide the meaning for our imagined community of millions. Now that’s what I call home.

Mark Perryman is co-founder of Philosophy Football, AKA ‘Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction. Our ‘imagined community of millions;’ T-shirt is available

Mark Perryman is co-founder of Philosophy Football, AKA ‘Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction. Our ‘imagined community of millions;’ T-shirt is available

from here.

Fields of Play

11.07.18

A first England World Cup semi-final for 28 years has Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman joining the dots between pitches and politics.

It seems like only yesterday that ‘Football’s Coming Home’ became England’s National Anthem, an England shirt our national dress and not being able to move for St George’s Cross Flags. 2018 is fast becoming the new ’96 and English hope springs eternal that this time there might be a happier ending too.

Football’s coming home, one of those fronting it is comedian and writer David Baddiel, born in New York, his Dad Welsh, his mum a refugee from Nazi Germany, Jewish. Neatly summing up the patchwork of identities most modern, and some ancient, icons of Englishness are constructed out of. When it was originally written the song was wrapped up in the mildly imperious idea that England is somehow the home of football, a message that framed the disastrous English bid to host World Cup 2006, an arrogance that resulted in a humiliatingly low vote, and irony of ironies who got it instead? Germany.

Twenty-two years later the song seems more of a joyful lament than back then. Willing the return of the World Cup to good old blighty’s shores, its been away for too long, far too long. Oh, and its got a catchy and easy to remember chorus, that helps.

Does any of this matter very much? Well actually in the big wide world outside of both Westminster and Planet Placard yes it does. The South African academic and activist Prishani Naidoo wrote ,whilst her country was hosting World Cup 2010, of football ; “ The field of play it produces stretches far beyond the boundaries of its goal posts and pitches – fields of play that sometimes bring into question the ‘taken-for-granted’, ‘the natural’, the ways in which ‘we are meant’ to be in society.” For many the most important event this week will be the very public falling out of Tory Ministers with each other over Brexit. For others the event they are most looking forward to is Friday’s march against Trump. Both, of course are hugely important but for millions of others it is all about England v Croatia and the sniff of a World Cup final appearance for the first time in 52 years.

Yes some have a stake in all three but a Left that aspires to be popular should be effortlessly making the connections, joining the dots between Wednesday night’s ‘field of play’ and that process of ‘bringing into question’. The football writer Barney Ronay has located the link superbly well ;

The FA neither owns nor controls the mechanics of grassroots football. It has no power to dictate what Premier League clubs do with young players. It isn’t the nation’s PE teacher. It is instead something of a patsy. One of the FA’s significant functions is to act as a kind of political merkin for the wider problem. Which is, simply access for all: the right to play, a form of shared national wealth that has been downgraded by those in power for decades.

These extremely wise words were written several years before World Cup 2018, rather, following yet another earlier-than-we-hoped-for exit . The first part of Barney’s argument has been addressed as far as they could by the FA. Unable to regulate the Premier League clubs treatment of young players they have invested heavily in their own under-age group teams with startling success. The core of Southgate’s squad have been playing for England junior teams since their teens, travelling away to tournaments, learning to get on with each other as well as play alongside each other. And of course Southgate for a period was their Under 21s manager too, with a watching brief on younger squads as well. His has proved an inspired appointment but one that within the constraints of free market football went alongside the FA re-asserting its role as a governing body, the game’s regulatory authority, if you like.

But the second part of the argument remains as sharply evident now as ever. Those England players who before the tournament revisited the primary and secondary schools where they first learnt their football would have found those institutions with hard-pressed PE departments, in plenty of cases school playing fields have been sold off, those that remain struggle for the finances to be kept properly maintained. The youth football set-ups where these players developed their talent before being spotted for bigger things, struggle to find public pitches to play on and are deprived of the resources to build their own facilities. This is the austerity-driven reality for all those inspired by Russia 2018, young and old, to lace up their boots and drag themselves away from the sofa, sport as not simply something to watch, but to play.

A radical commonsense politics connects the popular with the political. So here’s an idea. On the day of England’s biggest game in 28 years Jeremy Corbyn gives Brexit a rest, leaves the Trump-bashing until he arrives on our shores tomorrow and instead pops down his local park. Not to make the rather trite current Labour party offer of a national (sic) holiday should England win the World Cup, tho’ this does have the added bonus of getting the Scots and Welsh behind the team. Nor a New Labour style photo-opportunity, y’ know the one Blair doing the keep-uppies with Kevin Keegan. No, to make a serious-minded speech about playing-fields, their selling off by successive governments and how a politics of football for all is how we make this most wonderful of World Cup summers actually mean something. 1-0 to Labour and England to win. That will do me nicely thankyou very much.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder ofPhilosophy Football, aka ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’, their World Cup and other T-shirts can be found here

Here we go, again

06.07.18

With a World Cup quarter-Final on Saturday Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman dares to hope for England

For fans of a certain age we’ve been here before. World Cup 2002, England v Brazil in the quarters, 1-0 up then first Rivaldo equalises on the cusp of half-time before just after the break Ronaldinho scores what proved to be their winner. English hopes dashed, never mind, no disgrace going out to the eventual champions.

Four years later and it’s all about Rooney’s sending off, Ronaldo’s knowing wink to the Portuguese bench and another dismal English showing in a long list of the like in penalty-shoot-outs. Unbeaten with 10 men over 120 minutes, this one we could put down to a mix of bad luck and continental skulduggery.

In between, Euro 2004, England v Portugal. Rooney this time is tearing the opposition to shreds, goes off injured, and after battling their way to a 2-2 draw it was yet another English exit on penalties.

That little lot is all of twelve years, and more, ago now. Sven was the manager, Becksmania ruled, Michael Owen, who’d burst on to the international scene four years earlier at France ‘98 was world-class, when he wasn’t injured, and the teenage Rooney at Euro 2004 looked to be even better. The latter, when compared to his contemporary Ronaldo, never came close to fulfilling his world-beating potential however. Unarguably his first tournament, Euro 2004, was also Wayne’s best. As for Owen, injuries robbed him of his best moments, at World Cup 2006 going off injured in the first minute of England’s final group game versus Sweden effectively his most unfortunate of international swansongs.

Sven did his magnificent best to manage England to exceed all our best expectations. The two previous World Cups we’d gone out at the last sixteen stage, ’98, and failed to qualify, ’94, at Euro 2000 we’d exited at the Group stage. Sven’s was the era of our last so-called golden generation yet the team was fatally unbalanced by the overwhelming popular fixation with Beckham and all that Becksmania brought with it. Without being privy to their respective changing rooms it’s hard to be certain but every impression is that Southgate’s 2018 squad has a collectivity that England 2002-2006 sorely lacked.

The team being greater than any single individual has an echo in an era before the consumption of football, and just about everything else, wasn’t soaked in celebritification. Of course this isn’t entirely new, before Beckham there was George Best after all, aka ‘the fifth Beatle’. But perhaps the better reference point is the last time England won a World Cup quarter-final, Italia 90. The huge TV viewing figures, the street celebrations, an England football shirt as our national dress, days organised around World Cup kick off times, it had the lot. And Gazza. Only five years earlier after the Bradford Fire Disaster The Sunday Times had infamously described football as “ a slum sport played in slum stadiums increasingly watched by slum people, who deter decent folk from turning up.” Thanks a bunch. English club sides were banned from European competition indefinitely following the lethal trouble at the Heysel Liverpool v Juventus European Cup Final, the post Hillsbrorough disaster presumption was that the fans were guilty, its easy to blame the Sunand their ilk for the awful coverage but people at the time largely believed the kind of stuff, the paper printed. Football looked dead on its feet, and for 96 Liverpool fans at Hillsborough that was precisely the tragic consequence.

Italia ’90 transformed how football was perceived. Any trouble our fans were part of at the start of the tournament entirely forgotten thanks to evening after glorious evening with Gary Lineker. And to top it all, by the end of the year, thanks principally to the catastrophic unpopularity of her Poll Tax, Thatcher was out. But Thatcherism, and the Tory government, remained intact. What Thatcher had created during her 11-year Premiership was a neoliberal consensus founded on the market being king and de-regulation the swashbuckling way to manage both economy and society. Football wasn’t immune to any of this, the much fabled ‘people’s game’ as a description of the way it was run, a quaint fairy story to reassure ourselves with. In the space of jut two years following Italia ’90 the top division of the English game had effectively been sold off by the sport’s governing body, the FA, de-regulated in other words. The broadcaster’s billions would govern the sport’s elite level best interests from now on, while a similar sell-off of the European Cup to become the Champions, or more accurately rich runner’s ups, League would distort the domestic game still further towards the interests of the wealthiest clubs and their transnational ownerships. Free market football was the direct consequence of England’s Italia ’90 success.

One England World Cup campaign won’t change all that. Italia ’90 reignited the popular appeal of football, despite the preceding tragedies, the hostile attitudes, the attendant hooliganism, and worse, only for this to be marketised. Perhaps Russia 2018 might help remind us of the possibilities of a game liberated from what it has become. No single club can ever achieve this in the way a national team can. No club has the universal appeal across our nation that England has. And none will spark the flying, wearing, painted on a face of St George either. This is a mass, popular culture we dismiss, but also build up, at our peril. Some such as Jason Cowley in this week’s New Statesman see it as the reawakening of a progressive English nationalism or as he waggishly dubs it, “Gareth Southgate’s England.” Others such as Stuart Cartland , reflecting on England’s penalty-shoot out triumph for Culture Matters dismisses an over-enthusiastic draping of the progressive in St George “ I can’t help but dread how any English success only serves to embolden a sense of Englishness of the Conservative right.” The point surely though is to mobilise our resources of hope to shift the balance from Stuart’s pessimism towards the most progressively possible of Jason’s optimism. Both views are right, and both wrong.

Jim Sillars, then an SNP MP, put it way back when Scotland was qualifying for World Cups that football produces “ninety-minute nationalists”. Now, with Scotland amongst the international footballing also-rans, Scottish nationalism is an infinitely more potent political force than in the 1980s and 1990s, a civic nationalism that is broadly social-democratic too. Political forces and circumstances shaped this, not Scottish football’s Tartan Army. Scottish Nationalism is about a place, not primarily about race, it isn’t hung up on the martial and the imperial in the way Little Englandism is, with no sign post-Brexit of getting over that, at all. If football can provide a space for contesting such ideas then why on earth forsake, or even worse surrender, that space. A Left politics which ignores that opportunity is surely making a huge error. The question shouldn’t be whether but how. A win on Saturday against Sweden as good a place to start as any other. C’mon, and unapologetically, England.

Mark Perryman is co-founder of Philosophy Football, aka ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ our World Cup and other T-shirts can be found here

England Expects

03.07.18

As England prepare to take on Colombia tonight Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman outlines what we might or might not, be able to look forward to.

Illustration : Hugh Tisdale, Philosophy Football

The last time England got to this stage at a World Cup there was no happy ending. A 4-1 thrashing at the hands of Germany at South Africa 2010. Well at least we know that isn’t going to happen, Auf Wiedershenbefore the postcards, ouch!

Though it might do not to be too cocky. England have a decent record in the last sixteen round when not up against a top tier football nation. Beating Ecuador at World Cup 2006, Denmark in 2002, Belgium in 1990, Paraguay in 1986. But out of that lot the only time we then made it past the quarters to the semis was when at Italia’90 after beating Belgium in the last 16 we faced Cameroon, rather than a higher ranked team.

This is what makes the Russia 2018 campaign so mouth-watering a prospect. Beat Colombia and the quarter will be against Sweden or Switzerland. And with Spain dispatched England’s semi-final opponent would be Russia or Croatia. Arguably there has never been a World Cup like it for sending well-fancied former tournament winners home early, Germany now joined by the last sixteen exits of Argentina, Spain, and reigning European champions, Portugal.

But again, don’t lets go getting ahead of ourselves. Since England’s last World Cup semi-final appearance 28 years ago non top-tier football nations; Bulgaria, Sweden, Croatia, Turkey, South Korea, Portugal, those that have never won the World Cup or played in a final, have made it this far. England’s world standing never moved on after 1990. In these intervening almost three decades, we fell behind others and in the recent past have slipped back still further. Thus, Colombia, Sweden or Switzerland, Croatia or Russia can’t be taken as lightly as some might assume.

All those fancied teams going home early has opened up the tournament but something else has happened too. No African team made it into the last 16. Pelé’s prediction that an African team would win the World Cup by 2000 looks as far away as ever. And with only Japan making it through to the last sixteen, despite their plucky performance against Belgium, their eventual defeat means the same goes for Asia too. Football is a truly global game but the very top level remains a European-Latin American cartel with little obvious sign of that changing. World Cups have been won, since its inception, by a remarkably small number of teams. Apart from Brazil, Germany and Italy plus Uruguay’s rather ancient 1930 and 1950 tournament wins following England’s one and only triumph, newcomers Argentina have won the trophy twice, in 1978 and ’86. Three tournaments later host nation France lifted the trophy for the first and only time in ‘98, and another three tournaments later Spain did the same in 2010 but not again since. After the exits of Germany and Argentina, the failure of either four times winners Italy to qualify or Holland, who hold the unenviable record of making the most appearances in a World Cup Final without winning it, the best possible outcome from Russia 2018 would be for a nation that’s never won the World Cup to lift the trophy, or England, of course.

World Cup winners may be more or less unchanging yet something else has changed, for European teams in particular. When England won the World Cup in 1966 the team was all-white. 24 years later and the team that lined up once again to face West Germany in the ’90 semi-final included just two black players, Des Walker and Paul Parker. Another 28 years on and of the England team to face Columbia tonight more than half the line-up will be black or mixed race . Something when it happened at World Cup 2002 for the first time seemed so natural a development it barely merited a mention. And what is true of England, the same more or less goes for France, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany and Portugal too, teams made up of a patchwork of a nation’s migrant communities .

Of course the meaning and effect of all this can be overstated. At France ’98 Zinedine Zidane led arguably the greatest multicultural team of all to World Cup triumph and two years later the same at Euro 2000. But in 2002 Jean Marie Le Pen makes it into the final round of the French Presidential Election for the first time ever, polling almost 20% of the vote. And in 2017 Marine Le Pen achieved the same, this time attracting a third of the popular vote. But the point is that a St George Cross draped in the colours of multiculturalism has at least the potential for the beginnings of a journey away from racism. It has a reach and symbolism like no other, touching the parts of a nation’s soul no anti-racist placard thrust in our faces is ever going to This is the meaning of modern football and when England begin to scale the heights of 2018 World Cup ambition the reach of that message is amplified still further on a scale and in a manner that ’66 could never have done, and ’90 barely began. A popular Left politics must surely connect with such episodes as metaphor, to translate what we see on the pitch into the changes beyond the touchline we require to become a more equal society. So here’s my maxim for Jeremy Corbyn and his colleagues. If Labour cannot explain the meaning of the World Cup why should I listen to what the party has to tell me on how they’re going to fix the mess the NHS is in? Not the flimsy populism of Blair when he adopted the ‘Labour’s Coming Home’ message after England’s last tournament semi, Euro ‘96, but a political practice rooted in popular culture because here, more than anywhere else, ideas are not only formed, but also changed.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of Philosophy Football, self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’. TheirEngland Expects T-shirt is available from here

If a week is a long time in

22.06.18

As England prepare to take on Panama Philosophy Football’sMark Perryman draws some lessons from the first week of World Cup 2018

Image : Hugh Tisdale

It’s a well-worn footballing cliché that you can only beat the team in front of you. But England taking until the 91st minute to secure victory over Tunisia doesn’t look good. Nevertheless, with three points in the bag, and a widely-expected second victory against Panama on Sunday, England’s last 16 qualification might – might - have been secured by Monday, in which case, given the likely opponents of Senegal, Japan or Poland in the next round, thoughts will inevitably turn to a possible quarter-final.

Without doubt this is English progress, of sorts, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Our natural status is beaten quarter-finalists. Prior to that golden day in ’66 it was the best we’d ever done, and we’ve only bettered this once since, at Italia ’90 all of 28 years ago. Sven was the last England manager to get us to a quarter-final, at World Cups 2002 and 2006 (as well as at Euro 2004 in between). If we make it this time Gareth Southgate will have got us back to where we belong, amongst the top 8 World Cup nations, but probably still a long way short of being among the top 4. It was ever thus.

Thankfully the games are all being played out against the backdrop of a happy clappy Ros! Si! Ya! , despite the build-up full of dire predictions of heavy-handed policing, neo-Nazi hooligan gangs, racist attacks, homophobia and the grimmest environment imaginable. The build-up was the same for South Africa’s World Cup 2010. Muggings, car-jacking, and a race war was what travelling fans were promised. Nothing of the sort materialised. And again for Brazil 2014, political unrest combined with Faveladrug gangs was predicted to ruin the World Cup for the supporters. Once again, no such incidents occurred.

But before you know it, England will be preparing to head home, and the same lazy predications about the host nation will be being rolled out for next time.

And we’ll also have the same curious phenomenon that when the matches kick off we go from one extreme, destination hellhole, to another, football paradise.

The truth is Russia does have problems; an authoritarian regime, Greater Russian nationalism, massive inequalities of wealth distribution, racism, homophobia and a violent fan sub-culture. None of these were ever going to be allowed to ruin a World Cup which is Russia’s unmatchable opportunity to showcase the best of its nation to the world. And none of them have gone away either just because a game of football is underway. As with an England win, against Tunisia, the whistle blows and all sense of perspective is booted out of the window.

We already know it will be Qatar hosting the tournament in 2022, followed by the successful joint bid of USA, Canada and Mexico for 2026. And England is apparently considering a joint British bid for 2030 with the Scots and Welsh FAs, which will face competition from the Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay joint bid, and no doubt others. These tri-nation hosts are a result of the World Cup’s expansion from the current 32 team format to a gargantuan 48.

The global reach of football is continuing so some kind of increase is justified, as it was when the tournament grew first from 16 to 24 nations for Spain ‘82, then again to 32 for France ‘98 and the same since then. But 48 is too big a jump. It creates too massive a tournament, too many games (many of which will be meaningless), and too big a disparity in ability. 40 would have been a much better compromise, 8 groups of 5 rather than the current 8 groups of 4, a step-up of 8 teams as every previous expansion has been. Oh – and with all the extra places awarded to the under-represented continents, aka anywhere but Europe and South America (sorry Scotland!).

A more modest increase in competitor nations would also preserve the feasibility of single host nations. Every previous one has helped define how a World Cup is consumed and remembered almost as much as the football on the pitch and the eventual winner. The one exception, when Japan and South Korea jointly hosted World Cup 2002 just about worked, thanks to the extraordinary success of the Korean team and their Red Army of supporters as they reached the semis, though Japan largely defined the consumption of the football and Brazil’s eventual victory in the Tokyo final.

Here’s an idea. 2030 is the centenary World Cup. The first one took place in Uruguay and England, like most of the other European nations, shamefully chose to boycott it because South America was too far away and the footballing world revolves around Europe, or in England’s case, ourselves.

So why not award hosting 2030 now to Uruguay, and abandon the expensive and corruptible bidding process? The world of football could give every assistance to this one small nation to host it. It could organise it as a celebration of one hundred years’ worth of the growing international appeal of our game, the people’s game. It could fly in the face of all that FIFA has become.

Well - like an England semi (even my optimism of the will has its limits) we’re allowed our World Cup dreams, aren’t we?

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of Philosophy Football our England World Cup T-shirt is available from here

Thirty-two nations under a groove

14.06.18

Will the World Cup be an orgy of petty-minded nationalism? Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman doesn’t seem to think so.

Design : Hugh Tisdale

In between the matches from Russia over the next few weeks here’s a trivial pursuit question to test mates’ footballing knowledge. Which is the only World Cup squad with the entire list of players playing in their own country’s domestic league. Easy! Easy! England, of course, except it’s not just a knowledge of football that provides the answer but politics, history and culture too.

First, the domesticity of our players betrays a certain very English parochialism . More comfortable at home than abroad, Europe after all is a foreign country.

Secondly, the political economy of the game, aka English clubs apart pay heaps more dosh than most overseas outfits.

Thirdly, Anglo-superiority complex. Who in England’s 2018 squad would make it as a certain first team starter at a top German, Italian or Spanish club? Precious few, there’s a number who aren’t even regular starters at their own clubs, edged out by Johnny Foreigner’s talent.

More than anything else it is political economy which helps explains this.

England’s second most successful World Cup campaign remains Italia ’90. Of England’s starting line-up Lineker had played in Spain, for Barcelona, Waddle was then playing for Marseille in France. Gazza, Des Walker and Platt all went on to play for Italian clubs. And this was by no means unusual. And as for the victorious West Germany side who went on to win the trophy none of them played in England though Klinsmann would end up being snapped up by an English side but that was 4 years hence in ‘94.

The lesson that was drawn from Italia ’90 was that English football had the potential to recover its reputation and popularity post the banning of our club sides from European competition post-Heysel and the human tragedy of Hillsborough. How? This, like so much else after Thatcher’s election in ’79 until Jeremy Corbyn came along to break the spell of its appeal, was down to neo-liberal deregulation. The FA effectively gave up its right to govern the elite level of the game by floating off the top division, formerly the First Division and now the Premier League to be run by the clubs themselves. With Murdoch in hot pursuit following the dawning realisation that broadcasting live football was the only way to save his fledgling satellite TV company, Sky, the deregulation accelerated via the vast wealth TV contracts were to provide.

Neoliberalism isn’t the same as globalisation but they are intimately connected. The latter always producing a counter-reaction. In Donald Trump’s case this is his populist America First nationalism. Across Europe movements for independence, from Catalonia to Scotland. And throughout the same continent anti-migrant movements too. In football’s case it is the persistence influence of racism and worse amongst certain fan subcultures co-existing with the huge influx of foreign players. Again the World Cup illustrates this. Consulting once more my handy pocket-sized World Cup squads guide for reference a tasty looking English Premier League eleven out in Russia would line up like this; De Gea in goal, Mendy, Monreal and Christensen providing three at the back, Pogba, Eriksen, Hazard and De Bruyne packing the midfield, up front Firmino, Aguero, and Salah. And there’s plenty more where that lot came from too. Yet precious few fans in their right minds is going to complain about these particular migrant workers, over here, nicking our players’ jobs, with their foreign ways and the like. Racist attitudes to that extent marginalised.

A football club, up and down the divisions, stretching down into non-league even is easily the most globalised public institution in English society we can think of. The owners, the management and coaching staff, the aforementioned players, the fan-base, the sponsors and advertisers , the TV viewing public. All are globalised and apart from the most embittered few would object to that. This doesn’t mean the process is entirely unproblematic, football mythologises itself as the people’s game, it has never been thus, clubs owned by the local butcher baker and candlestick maker, in Man Utd’s case quite literally. The Edwards Family were butchers who sold the club they owned off to the Glazers, US sports moguls. A local business elite owned the game in their own local interest, the only difference now is that it’s a global business elite running it in their own trans-national interest.

Resistance to absent owners erupts from time to time, tho’ homegrown owners are often not much better, just look at West Ham. But what frames modern fan culture most of all is a popular cosmopolitanism. While England agonises over how and when it will exit Europe, every football club’s ambition is to get into Europe. This is our cultural barricade against the hateful rise of the Football Lads Alliance. Their values founded on division are the complete opposite to the way the modern game is consumed and supported . For every fan cheering on England over the next few weeks there will be others keeping an interested and supportive eye on how their club’s foreign players are doing, and most importantly many are fully capable of doing both. One nation, thirty-two nations, for the next three and a week under the same groove. For this precious moment nothing could be more powerful as a resistance to racism and division than that. And you know what despite FIFA’s worst efforts its broadly equitable too. What have the superpowers of the USA, Russia and China got in common? They’ve not got one World Cup between them. And that’s because international football is regulated, no country on earth however rich is ever going to persuade Messi, Neymar or Ronaldo to sign for them. If that’s not neoliberal globalisation turned on its economic head into something a tad better I don’t know what is.

The Thirty-Two Nations Philosophy Football T-shirt is available from here

The Corbyn Moment

05.03.18

Mark Perryman argues that now more than ever is the time to transform Labour into a social movement

In a week that my new best comrade George Osborne has described the impact

of Jeremy Corbyn’s Customs Union speech as “ The Labour leader, has with the

smallest of nudges, manoeuvred himself into a more pro-business, more pro-free

trade European policy than the Tory Government “ the question of whether this

marks the Corbyn Moment stretches way beyond the ranks of the Corbynite Left.

George meant those words as a compliment, their provenance and meaning will

however trouble many on Jeremy’s side. But this dear comrades is what

hegemony looks like, our ideas becoming the new common sense. And without

in essence even a smidgen of principle being sacrificed either.

Anyone who doubts the difference Jeremy has made, and continues to make, to

Labour politics should be force-fed Tony Blair’s 2005 Labour Conference Speech

to read. “I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as

well debate whether autumn should follow summer.” Thus, the economic powers

reshaping the world described as a force of nature, unstoppable, irresistible, no

point in expecting that they can be changed in any meaningful sense.

Of course Blair in government did many good things. Nobody in their

right, or left, minds should pretend otherwise. That’s what Labour in power is

expected to do isn’t it? But crippled by this embrace of neoliberalism the

measure of Blair’s failed promise would bedevil Brown and Miliband who

unsuccessfully followed in his wake. During the 2015 General Election

opposition party leaders debate Ed snapped back that he wasn’t the same as the

Tories under the torrent of the sisters united criticism from Nicola Sturgeon,

Leanne Wood and the Green’s Natalie Bennett. Quick as a flash Nicola tellingly

retorted that no Ed you’re not the same, but neither are you different enough.

Notwithstanding Osborne’s plaudits this is something nobody is ever going to

say about Jeremy Corbyn . And that’s why the next General Election will be so

momentous in the same way ’45 was, ushering in the post-war settlement, and

’79 not only ending it but carving out its replacement in the shape of

neoliberalism. A Corbyn government would put an end to all of that, for good.

To achieve this requires a laser-sharp campaigning focus on winning a minimum

of Labour’s 66 target seats and holding on to Labour’s 19 most precarious

defences , those with majorities of less than 1000. The 3rd May local elections will

be the first test of how far Labour still has to travel to not just come a decent

second, but to win. Despite all the chatter about a ‘Progressive Alliance’ via

tactical voting it is this kind of tactical campaigning that will secure a Labour

majority.

Meanwhile on the all-important ideological level it is hard to dispute, despite the

naysaying commentariat and backbiting from the Labour hard Right, Labour has

been setting the agenda almost from the moment the 8th June votes were

counted. Exposing the Tories getting into bed with the DUP as not so much a

coalition of chaos but the coalition from hell. Responding to the causes and

consequences of the Grenfell disaster. Standing up for an NHS facing the

impossible task of coping with a winter crisis as resources and morale wither

away. Locating the Carillion collapse in the rottenness of privatisation at any

cost. And now, most recently, outlining a way to navigate Brexit in a manner that

puts the haplessness of Johnson, Davis and Fox to utter shame.

But winning in 2022, or sooner if at all possible, is going to take all of this and

then some . It means the transformation of Labour into a social movement

on a quite unprecedented scale. We saw the beginnings of this last May and June

as marginal seats were flooded with eager, often new, campaigners to win the

Labour vote street by street and led by Owen Jones and Momentum this has

Continued ever since with regular #Unseat days of mass canvassing in the most

high profile of Labour’s target marginals. All this doorstep activity carried out

not as a dutybound stage army of the party’s extras but as a building block

towards a mass, members-led party rooted in our communities rather than the

entrenched deference of the parliamentary party.

For those stepped in the Labour tradition of Keir Hardie and Ellen Wilkinson, the hunger marches, Cable Street, the International Brigades, Stafford Cripps, Labour winning the peace in ’45, Bevan and the foundation of the NHS, Barbara Castle on the picket line with the women Ford strikers campaigning for equal pay, Foot, Kinnock and Benn leading CND demonstrations, Bernie Grant standing with his community after the ’85 Broadwater Farm riots, none of what I am describing here should appear either new or all that threatening. But for some it certainly seems as if the latter was precisely how they regard such a change, and 8th June 2017 has done precious little to alter their opinion either. They describe this as ‘Clause One Socialism’ and have the pin badges to prove it.

The grouping most identified with this Clause One position inside the Labour Party, Progress, puts it thus:

“ In the 1930s, 1950s and 1980s Labour was pulled away from its true path by syndicalist social movements. At its founding, the party’s intention was clearly spelled out for the world to see in the very first paragraph of the constitution: to ‘maintain in parliament … a political Labour Party’”

Contrast this with the symbolism of who was called upon to introduce Jeremy Corbyn at the final big outdoor rally of the 2017 General Election Campaign, Saffiyah Khan. A few months previously the photo of Saffiyah, a young Asian, Muslim woman fearlessly facing down the English Defence League boot boys in her Birmingham town, peacefully with a smile on her face had gone viral. She had stood up for what she knew was right. Neither parliamentarianism nor protest politics can do that on their own, rather it needs Saffiyah and hundreds of thousands like her to make such resistance possible. Not a stage army at anyone’s beck and call but individuals who come together and create communities of change. That’s the party Labour might become, and if it does just about anything is possible. Now that’s not something I suspect George and his big business mates will welcome with such open arms as Labour’s commitment to a Customs Union. And in the greater scale of things that is what both really matters and will shape Labour’s future.

Mark Perryman is the editor of The Corbyn Effect and will be speaking at ‘The Corbyn Moment ’ a day of discussion and debate on Labour as a social movement featuring Alex Nunns, Andrew Murray, Francesca Martinez, Hilary Wainwright and others. Saturday 10 March, London. Organised by Counterfire, further details and booking tickets from here

#We Were Many - Philosophy Football's Review of 2017

31.12.17

Backed by what was undoubtedly the tune of the year Philosophy Football chooses images that record 2017 as twelve months of resistance and sometimes change

Wow! 2017, twelve months of surprises, mostly unpleasant some not so. At its core all things Trump who since his presidential inauguration at the start of the year has managed to fulfil all our worst fears of what his time in the White House would come to represent.#ToryBrexit more or less achieved the same mix of reaction and risk yet June came close enough to ending May to give us a belief that a very different outcome may yet prove possible. Jeremy Corbyn's Labour 'For the Many not the Few' summing up the possibility of an alternative to austerity we witness daily with the growth of foodbanks, and the spead of a low-wage casualised economy. The consequences of putting profit over people, the human tragedy of Grenfell. But it doesn't have to be like this. Trump's racism was rejected by the 'take a knee' movement,#MeToo turned one man's horrific treatment of women into a movement to resist and transform, Corbyn's Labour was written off at the start of#GE2017 now it is a serious contender for government.

The continuing, and increasingly devastating, impact of Climate Change could mean us having nothing much to look forward to but everytime we prove we are many, they are few there is hope. If one image of 2017 captured this it was the calm, courageous dignity with which Saffiya Khan stood up to the hateful EDL when they came to her city. With that spirit shared by we, the many, in 2018, neoliberalism won't just be broken, it will be replaced by something better. Happy New Year!

From Bah Humbug to Oh Jeremy Corbyn

15.12.2017

Never mind miserabilism this Christmas MARK PERRYMAN discovers more than enough books that described reasons to be cheerful

Trump, the threat of nuclear war with North Korea, an unfolding sexual harassment scandal, the human tragedy of Grenfell, a weak and wobbly government shored up by a coalition of hell with the DUP. All good enough reasons to have a pretty bleak view of the world in 2017. But Christmas, whatever our faith or none, is a time of hope, so my selection of the year’s most compelling political books tends to err on the side of hopefulness, with no apologies.

There’s plenty of the customary mix of pessimistic intellect and optimistic will in the sublimely good, and substantially, updated post-election second edition of Richard Seymour’s Corbyn : The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics. For a practical insight into how that radical politics is being organised in and around Labour The Way of the Activist by Jamie Driscoll and Rachel Broadbent, published by the excellent Talk Socialism political education group, provides a how-to guide which is rare in the scale of its imagination and ambition. Chris Nineham’s How The Establishment Lost Controlbuilds on his earlier account of the Stop the War movement The People v Tony Blair to make a case for a left politics that is rooted in the movement rather than the party. The issue for me is whether without the leverage a well-organised left within Labour, yet open to the movements Chris describes, change can be effected. John Medhurst’s That Option No Other Exists since it was published in 2014 has become the definitive account of both the necessities for such a Labour Left but the limitations therein too. Perhaps the best way of combining both options, in but not restricted by Labour, is the popularising of radical ideas, there’s few better starting points for such an objective than George Monbiot’s latest book Out of the Wreckagewhich describes its purpose as “ a new politics for an age of crisis.” Or perhaps it's best this Christmas simply to sit back, kick off the slippers and reflect on how the past twenty years has ended up with Jeremy Corbyn (Jeremy Corbyn!) closer to Number Ten than anyone ,including himself, could ever have imagined. John O’Farrell tells the story of those two decades with his own unique, and richly amusing, style in Things Can Only Get Worse? And as for where it all started, Richard Power Sayeed establishes himself as the definitive critical chronicler of the Blair years with his superb book 1997: The Future That Never Happened.

If we can agree that to make a success of Corbynism demands a wider perspective that both includes Labour but goes beyond it too then to help us to understand the nature of the politics this now demands is Platform Capitalism by Nick Srnicek which provides an overview of the economic terrain on which Labour would seek to govern for the many, and all that. To come anywhere close to fulfilling that aim will require reinventing what we mean by the collective, aka ‘the many’. A process made a tad easier following a reading of Lynne Segal’s new book Radical Happjness a project she describes as rediscovering processes towards creating ‘moments of collective joy.’ The Mask and The Flag by Paulo Gerbaudo foregrounds the thinking of a new generation of activist-intellectuals as they seek to map out a similar project towards new forms of collective action. The collection Beautiful Rising showcases this process on a global scale with one inspiring example after another to leave campaigners breathless with the belief that abother world remains possible. One domestic example of this sort of resistance were the 2010-11 protests against the tripling of tuition fees, a story now retold in Student Revolt by Matt Myers. Matt describes the lasting political legacy of these protests as an ‘austerity generation’ many of whom are now supportive of, and involved in, Corbynism. But the broader impact remains the wholesale, and disastrous marketisation of higher education, the consequences of which are powerfully accounted for by Sinéad Murphy in her book Zombie University, a right horror show. None of this pales into insignificance, of course, compared toTrump’s Presidential reign but his brand of reaction has proved more than bad enough to dominate much of 2017 . Why Bad Governments Happen To Good People is Danny Katch’s handy explanation of how America ended up with Trump in charge.

In Britain meanwhile the next General Election, barring a major miracle, will be fought post-Brexit. So understanding the likely impact of this rupture is vital in preparing for Labour not just to do better next time but to win. In The Lure of Greatness author Anthony Barnett gets away from the liberals’ blame game to explain why Brexit happened and carves out a future politics that can reverse those reasons. But before we get there there’s a very real likelihood of things turning nasty, with food prices, even shortages too, quite possibly at the centre of such tensions. Bittersweet Brexit by Charlie Clutterbuck is the first serious attempt to explore the #ToryBrexit consequences for farming, land and food inflation. One of the chief architects of this almighty ‘uck up is Boris. For too long treated as a loveable rogue he is in fact both hapless and dangerous, a lethal combination brilliantly exposed in Douglas Murphy’s account of his tenure (sic) as London Mayor Nincompoopolis. Is there any way out of the mess? Harry Leslie Smith’s powerfully written Don’t Let My Past Be Your Future continues this ninetysomething author’s effort towards a call to arms (of the metaphorical variety) with a passion and poignancy still all too rare in our body politic. Stuart Maconie revisits that past which framed Harry’s lifetime of views with his Long Road from Jarrow an imaginative tracing of the 1936 Jarrow March, then and now Or for a very different take on how the legacy of yesteryear’s politics shapes the politics of today and tomorrow try the innovative, and very challenging approach of Revolutionary Keywords for a New Left where author Ian Parker offers a redefinition of the vocabulary of change, A-Z.

Precious few writers manage to effortlessly mix popular culture with radical politics. Yet without that combination any prospect of change is seriously reduced. One author who did was David Widgery, a selection of whose writings have been re-issued with the great title Against Miserabilism. One of the finest current exponents of making these kinds of connections is Laurie Penny, her latest book of essays is Bitch Doctrineand not one of them fails to impress with the sharpness of wit, tone and politics. A towering influence over making connection of politics and culture indvisible remains Stuart Hall and it is therefore hugely welcome that following other recent collections of Stuart’s work a new selection has been published of his lectures on race, ethnicity and nation The Fateful Triangle. In this era of the revival of a populist-racist Right this is an absolutely essential read towards what Stuart Hall once described as an ‘alternative logic.’

The Left, me included, has a bit of a thing about its own history. For some this is an unhealthy obsession with unchanging certainties. For others a breathless modernisatiin which defines itself by junking the past simply because it old not new. What considering our past of course should be about is not being trapped by it but beng liberated by our history via an exploration of what became possible and what proved to be impossible. Hence a favourite journal of mine is Twentieth Century Communism the latest edition uses the 1917 Centenary to revisit the differing politics of previous commemorations, testament to the journal’s unpredictable breadth, and insightful depth. A similar, but even wider approach is taken by the journal’s special edition Echoes of October ranging even wider over the period of commemorations from 1918 to 1990 with Ukraine in the 1920s Weimar Germany and Pravda amongst those included. A very different approach is taken by a long-time supporter of Philosophy Football Pete Ayrton with Revolution! A really revealing collection of original writing from those Ten Days that shook the proverbial one hundred years ago. Available as an exclusive signed first edition from here. A challenging account of 1917 is provided by John Medhurst’s No Less Than Mystic a deconstruction of the history which is both scathing of the errors made yet incontrovertibly optimistic of the unfulfilled potential. Of course any account of the Communist tradition has to be about more than just 1917. Another special edition from Twentieth Century Communism Weimar Communism details the extraordinary rise of the most powerful post-1917 Communist Party outside of revolutionary Russia, the German Communist Party, and its eventual eclipse by the parallel rise of Hitler’s Nazi party. A splendidly different account is provided in Red International and Black Caribbean by Margaret Stevens where she uncovers the largely hidden history of Communist organisation in Mexico, the West Indies and New York City during the inter-war years, 1919-1939. Of course the period since 1945, and again since ’89, has convulsed whatever remained of the Communist ideal after those early days shaking the world. Mike Makin-Waite’s Communism and Democracy provides an insightfully original account of the twists, turns and missed opportunities from there to here without ever losing sight what remains alive, if not always kicking. The second volume edited by Evan Smith and Matthew Worley on the British Far Left Waiting for the Revolution is an account of post 1956 communists and revolutionaries of various varieties who lost their way on more than one occasion but for all that kept on, keeping on, a persistence which isn’t all bad, or all good either, and this collection helps us to understand why.

But none of this historiography makes much sense if in the process the personal is divorced from the political. Michael Rosen’s So They Call You Pisher? avoids the latter pitfall. As a memoir of growing up in a London East End Jewish Communist household the book combines sublimely a rich humour and a sharp politics with good writing which is such a rare combination in most left writing , and that’s a great shame.

The mix of radical politics with popular culture remains a constant, yet necessary struggle. It is something on the whole Corbynism remains rather weak on considering the huge potential. This is another instance where valuable lessons can be learnt from history, not to slavishly replicate earlier models but to recreate for the times in which we live now the ideals that fused these cultures of resistance back then. One such example is retold by Rick Blackman in his short book Forty Miles of Bad Road which uncovers how musicians came together to help promote unity after the 1958 Notting Hill Race Riots. A perhaps more familiar era is revisited by Matthew Worley’s No Future detailing the collision of punk, politics and youth culture 1976-84. Heady days for those who lived through them and invaluable towards understanding the potential for something of the sort, similar but different, today. Grime4Cobyn and the We Shall Overcome Weekend fesitvial beng just two examples from 2017 of the possibilities.

One possible fusion of the political and the cultural is poetry. Rosy Carrick’s new edition of the epic Mayakovsky poem Valdimir Ilyich Lenin is 197 pages’ worth proof positive of that. Or for a more current exponent look no further than Michael Rosen (again) and his latest poetry collection Listening to a Pogrom on the Radio. Not that there aren’t plenty more from where Michael is coming from, the Bread and Roses 2017 Poetry Anthology On Fighting On! brings together a selection of just some of the many wordsmiths working on the poetry front versus reaction, and the evidence here suggests, to very good effect. With a thriving spoken word live scene too, and the work of groups like Picket LIne Poets and Nymphs and Thugs, another invaluable resource of hope towards a better future.

And amongst all this reading what about something for the children? Detective Nosegoode and The Museum Robberyby Polish children’s author Marian Orton´ is every bit as good as the previous two in this series for junior crimefighters. A newly revised version of a familiar tale of all things Scroogelike Michael Rosen’s (yes, that man again) Bah! Humbug! is of course an absolute seasonal treat.

Apart from all these reads for the most stylishly political stocking-filler this year’s Verso Radical Diary is every much a must-have as the 2017 debut edition.

And the political book of this seasonal quarter? After the year we’ve had combined with a passion for mixing politics, popular culture and humour there was only ever one contender. Incredibly original, with a vast range of wonderful artists contributing, The Corbyn Comic Book funny, touching and meaningful. And looking forwards, or Oh 2017... as the New Years's Eve song, might go what could next year possibly bring?

Note No links in the review are to Amazon, if you can avoid buying from tax dodgers please do.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self styled sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction aka Philosophy Football. His own book The Corbyn Effect was published in 2017 and is available from here

- And then there were two

01.03.25 - This Land is (still) Your Land

22.02.25 - Happy 80th Birthday Bob Marley

01.02.25