A National Reality Check

14.07.18

With no England World Cup Final to look forward to this weekend Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman looks back in hope

Illustration : Hugh Tisdale

On the eve of World Cup 2010 a book with just about my least favourite title of all time, Why England Lose, was published. Never mind, it proved to be an excellent read though as anyone who can remember our last sixteen 1-4 thrashing at the hands of Germany the book didn’t exactly have a happy ending.

The book, now repackaged with a more sales-friendly title Soccernomics, regardless is a great read. The theory of England’s losses begins with what is now a fairly familiar recounting of England’s World Cup record which despite 2018’s glories remains at best quarter-finalists on the whole. We’ll have to go some in 2022 and beyond that to reverse that historic pattern. The points about recruiting from a narrow base of the population have moved on quite a bit too, with an admirably diverse squad. Cue the hurt shrieks of the ‘political correctness gone mad’ brigade. No, its just that if you want to succeed draw on the widest possible talent pool, are we doing enough to talent-spot youngsters starting out in the game from the sizeable Asian, Chinese and East European migrant communities? That’s the question youth football coaches and scouts should be asking themselves. The authors of the book, Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski, make an additional point however about our talent pool. Why do almost all England players come from a working class family background. In 2010 the only England player from a middle class family they found was Peter Crouch, his dad a creative director at an international advertising agency. My alternative view would be that this remains football’s enduring appeal, despite the gentrification of how it is consumed and marketed the players are working-class connecting it at least in part to its roots as the people’s game.

The main part of their thesis however was explaining World Cup success in terms of the victorious nation’s size of population and ratio of registered professional players to the that overall total (thus ruling out the likes of USA, China and India). England’ top eight status but not perennial semis, finalists or winners therefore seems about right. And in quasi-Marxist terms this amounts to an admirably materialist, if for England fans depressing, analysis. But what about Croatia, population 4.2 million, Belgium, 11.4 million. Croatia will be the smallest nation in a World Cup Final since Uruguay’s successes in 1950 and 1930, and bear in mind the World Cup was a very different competition back then too.

During the course of this tournament Simon updated his analysis to prove an additional explanation for the apparent Belgian anomaly:

“ Most of today’s Devils (the nickname for the teams is The Red Devils) have been globalised since their teens when the emigrated to learn football in nearby countries. The are multilingual and largely above the Flemish-Walloon divide.”

A multicultural team not afraid either of being cosmopolitan about where it both learns and plays its football. Something similar can be said of Croatia. Far more mono-cultural than Belgium’s squad they are nevertheless smart enough to recruit from players whose families became refugees from the Balkans war but who’s sons want to play for their homeland. Croatian international Ivan Rakitic who grew up in Switzerland being perhaps the most obvious example. But Croatia’s starting eleven also included homegrown players who now turn out for the top European teams, Real Madrid, Juventus, Inter Milan. And Liverpool.

Again it’s a materialist analysis that makes a lot of sense. English players who stick at home, in a top division that confuses being the richest league in the world with being the best, lack that dimension, pitting themselves against different styles, subjecting themselves to coaching and management approaches they might otherwise not experience, learning to live in another country, picking up a foreign langue, or three. Too many foreign players and managers over here? Until our England internationals choose to leave the comforts of home thanks to them its the closest thing we have to the globalised footballing cultures other nations benefit from.

That’s the materialism accounted for. We could add the good fortune of the almost entire absence of injuries and suspensions. England have never been so lucky on both fronts before but lets be generous and put that down to good planning, better sports science than previously and an improved disciplinary record.

It is the other key factor that is much harder to root in any version of materialism. The luck of the draw. Every single time before England finishing second in their group condemned them to a really tough quarter-final and in some cases almost as tough an opponent to beat at the last sixteen stage too. In Russia after finishing second in their group the combined might of former winners Brazil, Argentina, France, Spain and Uruguay plus reigning European Champions Portugal were all in the other half of the draw and couldn’t be played until the Final. When we faced teams in our half with half-decent rankings, Colombia and Croatia, we either failed to beat them over 120 minutes or lost. It is hard to imagine England will face such a fortunate draw for a long time to come. And if Germany, Italy and the Netherlands get halfway close to restoring themselves to former glories the task becomes that much harder again.

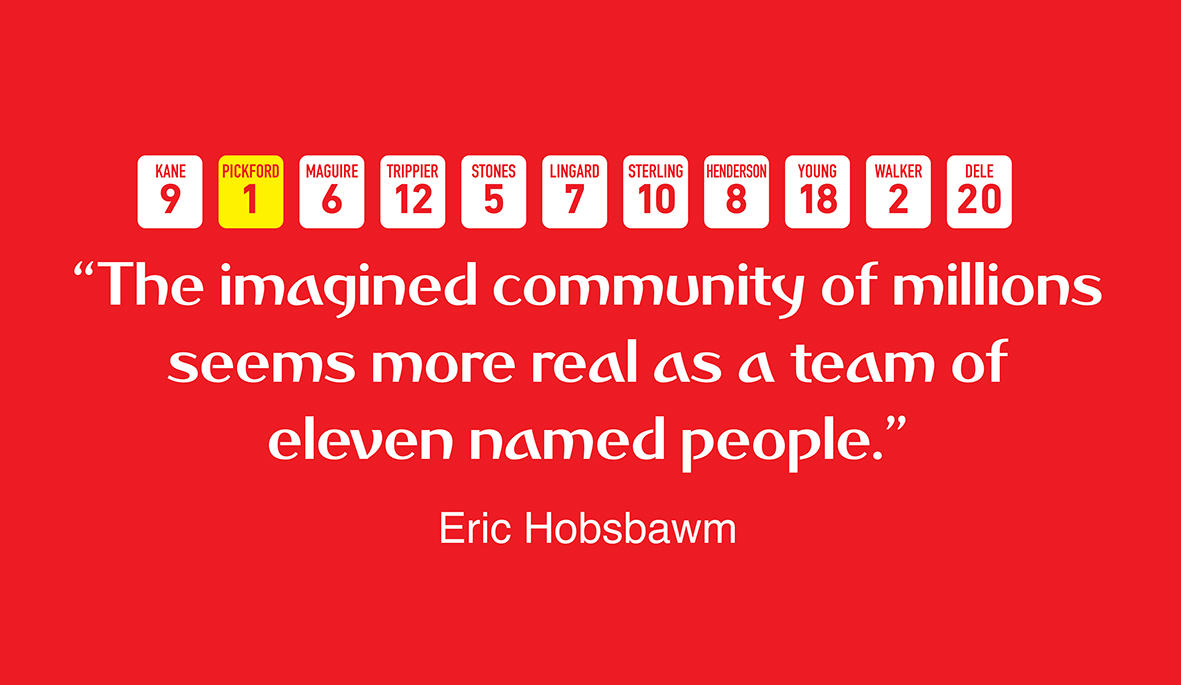

Is this a case therefore of just enjoying England while it lasts. No, not all. A young squad, a manager with a sense of purpose, together with the fans this summer we’ve all written our own history. Always looking backwards, to ’66 and ’90 not forwards, more than a bit laid to rest. If we’re looking for a 2018 legacy this surely is the one to build on, one we can affect. No more looking nostalgic as our national comfort blanket, one that is invariably, and uncomfortably, confused with an imperial, a martial, and racialised history. The past after all is a different country. Instead for the last four and a bit weeks we’ve had eleven named people and their best, with us chering them on, to provide the meaning for our imagined community of millions. Now that’s what I call home.

Mark Perryman is co-founder of Philosophy Football, AKA ‘Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction. Our ‘imagined community of millions;’ T-shirt is available

Mark Perryman is co-founder of Philosophy Football, AKA ‘Sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction. Our ‘imagined community of millions;’ T-shirt is available

from here.