Ten Books to Shake 2020

07.02.20

Want to turn the world upside down in 2020? Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman has found ten books to help us on the way

1. Naomi Klein On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal

The issue that should have dominated the 2019 General Election, but didn’t, the climate emergency. Despite this it’s not going to go away, the Australian bush fires are simply the preview of long hot summers to come Europe’s way and ever increasing risks of floods too. Naomi Klein wears Trump’s ‘prophet of doom’ badge with honour and in her new book On Fire is unafraid to map out a planet on the verge of a breakdown with a plan to do something about it.

2. Ann Pettifor The Case for the Green New Deal

A small group of economists have been working on a ‘Green New Deal’ since the mid 2010’s. The idea was revived and made popular first by the Democrat’s Alexandria Ocasio Cortez early championing of the idea on her election to Congress in 2018 and then once more last as the highlight of Labour’s 2019 General Election Manifesto. A read of Ann Pettifor’s The Case for the Green New Deal , Ann was one of that original small group, serves to inform and inspire a politics of alternatives to the otherwise forthcoming destruction of our planet.

3. Jack Shenker Now We Have Your Attention

While it is absolutely right to seek to establish a common-sense understanding that the Climate Emergency changes everything this won’t happen by ignoring the fact that for most life goes on, not regardless, but because there is no other choice. Now We Have Your Attention by Jack Shenker is a guidebook to this stark reality. The precariat, hollowed out communities, a debt-ridden generation, but also day-to-ay resistance by casual workers, renters’ unions, grassroots Labour members. A book to both make sense of, and change, the world.

4. Maya Goodfellow Hostile Environment : How Immigrants Became Scapegoats

There’s not much doubt that the four years of the Brexit Impasse has ramped up a resurgent, populist racism . That’s not to say Brexit is a racist project, it isn’t, but too much of the discourse around it plainly is. And that in turn built on the legitimising of racism via government policy to create, remarkably in its own official words, a ‘hostile environment’. Maya Goodfellow’s Hostile Environment expertly unpicks the background of how 2020’s racism has been framed by this process and the widespread failure to challenge the basis of it.

5. Andrew Murray The Fall and Rise of the British Left

It might be thought in some quarters publishing a book on the eve of the 2019 General Election entitled The Fall and Rise of the British Left would mean only one thing in 2020, the remainder bins. But Andrew Murray, quite rightly, is of the school of thought that takes the long view. We are where we are, doesn’t mean that’s where we’ll stay. His account starts in the early 1970s to track this fall and rise through to the eve of the election. The downs of more immediate relevance right now, the ups might have to wait.

6. Daniel Sonabend We Fight Fascists : The 43 Group and Their Forgotten Battle for Post-War Britain

For an inspiring take on the art of the possible Daniel Sonabend’s We Fight Fascists cannot be bettered. The largely hidden history of the Jewish ex-servicemen who on their return to Britain from the war witnessed Oswald Mosley’s attempted comeback and set out to stop it, by any means necessary but mainly hard faced, well-organised, physical confrontation. Not for the politically faint-hearted, have a milk shake handy whilst reading.

7. Greg Philo, Mike Berry, Justin Schlosberg , Antony Lerman, David Miller Bad News for Labour : Antisemitism, The Party and Public Belief

What would the 43 Group make of the Labour Party being portrayed as an antisemitic party? The rigour of the approach by the media studies academic authors of Bad News for Labour cannot be faulted, there is so much detail here that much is obvious. But what is lacking is a broader political perspective, there should be no ifs, no buts, no need to qualify or contextualise our opposition to all forms of racism, and that includes antisemitism. Even, and arguably especially, when those victims aren’t allies of the Left on the question of Palestine. The really bad news for Labour is that too often, too many have appeared to fail that simple test.

8. Renewal : A Journal of Social Democracy

OK strictly speaking not a book, but a journal published quarterly. However add four issues of Renewal together in the course of a year to receive the best, and most up to date, debate and analysis of Labour politics from a left social-democratic standpoint. Which given the current trials and tribulations of the Labour Party, the shallowness of the debate therein, and the uncertain direction of the party thereafter makes Renewal uniquely placed to provide an indispensable read in 2020.

9. Nathalie Olah Steal as Much as You Can : How To Win the Culture Wars in an Age of Austerity

Steal as Much as You Can has to be the runaway winner of the best book title for essential 2020 reads. Nathalie Olah has written an effortless traversal of the terrains of politics and culture, unpicking their mutual reconstitution in the grip of austerity and neoliberalism. A book that never surrenders to left miserabilism, instead offering the kind of manifesto of generational hope that 2020 demands. And along the way unafraid to pay off its intellectual debts, to Stuart Hall and Mark Fisher in particular. What’s not to like?

10. Alex Niven New Model, Island : How To Build a Radical Culture Beyond the Idea of England

As soon as Rebecca Long-Bailey inserted the words ‘progressive patriotism’ into her pitch for the Labour leadership all ideological hell was let loose from that part of the Left that holds dear to the idea that ‘there’s nothing progressive about patriotism’ end of. Alex Niven is deeply suspicious of the idea of inserting ‘Englishness’ into all of this, yet ironically in New Model Island he reveals a keener sense of England than most. What he favours is a resurgent regionalism, let a thousand ‘Englands’ flower, to create what the book proclaims a ‘dream archipelago.’ As Britain stands, post-Brexit, on the verge of a constitutional collapse New Model Island is the essential guide to the troubled year ahead.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football

‘Cause London is Drowning

13.12.2019

… And I live by the river. Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman recalls an epic album

14.12.1979 The year of Thatcher’s election was seen out with the release of London Calling widely regarded as the finest of all Clash albums. 14.12.2019 forty years later another Tory nightmare begins. Seems timely to look back, in hope.

The Clash had burst on to the fast-emerging punk scene in ’77 with their debut album. The band’s second long-player Give ‘Em Enough Rope was released to mixed reviews. Over-produced, the tracks’ raw energy edge somewhat blunted. All this was to change however with London Calling.

From double album length, weighing in at astonishing nineteen tracks across four sides, to the stunning cover pic of Paul Simonon doing some serious damage to his bass guitar, this was to become an instant classic. The rich mix of sounds showcased the foursome’s ever-expanding musical influences; jazz, reggae and dub, the blues, rockabilly, ska. This by and large wasn’t what as expected of 1970s English punk bands. Despite that, both fans and critics loved it.

On their debut album Joe Strummer had belted out the anthemic ‘ We’re so bored with the USA’ yet two years later The Clash appeared to have fallen hopelessly in love with the place. The influences were obvious, from Montgomery Clift to Cadillacs, a wholesome embrace of Americana minus the shrill anti-Americanism of the band’s more obvious politics.

The band were emerging as fulsome internationalists too. Every bit at home belting out their tribute to inner-city resistance The Guns of Brixton as their very particular account of the battle against Franco’ fascists Spanish Bombs. For many listeners these would be their first introduction to either subject, The Clash were a genuinely educative, as well as innovative, outfit, a key influence shaping a generation who’s politics were framed by being anti-Thatcher on the home front and soon enough against Reagan on the global front too. Sounds, familiar?

Two tracks in particular stand out. Not only as unforgettable when first heard but uncannily prescient four decades on too.

"What are we gonna do now?

Taking off his turban, they said, 'is this man a Jew?'

'Cause they're working for the clampdown

They put up a poster saying: 'We earn more than you'

We're working for the clampdown

“We're working for the clampdown

We will teach our twisted speech

To the young believers

We will train our blue-eyed men

To be young believers."

A clampdown that mixes authoritarianism, race hatred and economic power. This was what the Clash railed against in 1979, it remains the shape of Johnson and Trump’s resurgent right-wing, racist populism today.

And then of course the album’s title track, London Calling

“London calling to the faraway towns

Now war is declared and battle come down”

This was the era of a Winter of Discontent, the Special Patrol Group, war in Ireland, and soon enough war in the South Atlantic too, the Nazi National Front on the march, Brixton and Toxteth ablaze, civil disobedience against Reagan and Thatcher’s nuclear arms race, the year-long Miners strike. ‘War is declared’, they weren’t far wrong.

"The ice age is coming, the sun is zooming in

Meltdown expected, the wheat is growin' thin

Engines stop running, but I have no fear

'Cause London is drowning, and I, I live by the river”

The meteorology might be a tad skewiff but a frightening vision of the future four decades on has become the vivid reality of the present-day climate emergency. A melting polar ice cap, record-breaking heatwaves, agriculture growing seasons in crisis, rising seal levels. Live by the river no longer such good advice mind when the ensure planet is on the verge of drowning. And we can rest assured The Clash of yesteryear would have been playing Extinction Rebellion benefit gigs today. Revolution Rock? ’79 vintage, play it loud, 2019 keep the faith.

Original image by Hugh Tisdale, Philosophy Football, available as individually limited edition print signed by Hugh here

Philosophy Football’s 40th anniversary London Calling T-shirt is available from here

How to Read an Election

28.11.19

Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman provides a handy reading guide for the 12th December General Election

There’s not much doubt politics is getting hot, hotter, hottest just as the nights draw in and get cold, cold, colder as Boris Johnson seek to bring some kind of ending to the sorry saga of all things Brexit.

A December General Election? The first at this time of year for goodness knows how long. And sort out Brexit? Well the last one didn’t, and there’s absolutely no guarantee the result of this one will either, whichever way it goes.

In the immediate aftermath of ‘17 there was much talk that for Labour it was the manifesto that wot (nearly) won it. Mike Phipps’ For The Many helps us understand the original’s appeal and the ideas required to win this time. Most of the contributors to the essay selection Rethinking Britain are slightly more detached from the organised Labour Left than those contributing to Mike’s book tho’ they share the same intent ‘for the many’, ranging over economics, employment, investment, and social security. One of the brightest voices for such a brand of ‘new’ economics is Grace Blakeley, her first book Stolen is a compelling account not only of all that’s wrong with how financial power is misused but also what could be done about it. The abolition of tuition fees was a vote-winner in 2017, makes good sense but surely we also need to ask what are universities for, not just how they’re being paid for. A good step in the former direction is provided by Raewyn Connell’s The Good University complete with rather excellent sub-title ‘ what universities actually do and why it’s time for radical change. My favourite source for ideas in and around Labour however is the quarterly journal Renewal issue after issue it never disappoints the latest issue is themed around the issue of democracy with a stand-out essay by Lewis Bassett on the vexed question of democracy in the Labour Party.

Radical, new, policies broke through at Labour’s 2019 party conference including the 4-day week, abolition of private schools, a green new deal. Most of these have found their way into Labour’s 2019 manifesto, good. But in any General Election these face the problem of how they are affected by the Brexit Impasse which isn’t going to disappear in a hurry, and hasn’t. And of course Labour’s antisemitism crisis will be an issue too. Strange Hate by Keith Kahn-Harris firmly and correctly puts the resolution of that crisis in the context of anti-racism. While for those unfamiliar with the specificities of Jewish culture A Jewdas Haggadah provides a much-needed introduction, with occasional hilarious results.

For a primer chronicling the history of the rise of Corbynism read David Kogan’s Protest and Power : The Battle for the Labour Party. As to what happens if Labour wins, Christine Berry and Joe Guinan’s People Get Ready! deals strategically with how Labour might govern while seeking to implement a post-neoliberal economic strategy unimaginably radical in it ambition. Wow.

But to get even close to that point Labour’s arguments for ‘real change’ need both to be made popular and to challenge a resurgent right-wing racist populism. J.A.Smith’s Other People’s Politics charts precisely this terrain via a rigorous deconstruction of the populist surge and what kind of response from Labour this requires.

Labour’s ‘Momentum Left’ is often derided as extremist, Marxist, in fact it is overwhelmingly non-marxist, Marxism no longer offers the pole of attraction for those who favour politics against the mainstream that it once did. In its place a greater range of models of critique. But that’s not to suggest it is ead, buried or irrelevant. The Corbyn Project by John Rees is testament to the necessity of a Marxist critique of even the most left-wing versions of reformism,. We can choose to differ with the critique but to ignore it entirely a serious error. The new edition of the classic Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein The Labour Party : A Marxist History now updated by Charlie Kimber to take in both the Blair-Brown years and Corbynism, carefully records from a Marxist standpoint the errors Labour governments have made over the decades. Again we can differ over the precise nature of the causes and consequences, but those causes and consequences need accounting for.

If Marxism is no longer sufficient to explain the modern world that doesn’t mean as a framework of analysis it should be made henceforth redundant. Testament to that proposition is the sharply titled, and written, Aaron Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism . Full of techno-politics of an unashamedly left complexion the book is described as ‘a manifesto’. Notwithstanding the free broadband offer not quite the version Labour’s produced, Labour still doesn’t entirely share Aaron’s, at times breathless, enthusiasm for the progressive potential of technological change is a tad breathless. Fair enough tho’ modern politics needs to understand how digital technology is transforming the terrain on which we contest. An unpicking of the contradictions this generates is provided by Jamie Woodcock’s Marx at the Arcade a careful survey of video games and the politics they produce.

Another ‘unofficial’ manifesto is The Socialist Manifesto by Bhaskar Sunkara who offers up a political platform historic in inspiration, futuristic in vision, practical for the present. In a similar vein Nancy Fraser’s The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot be Born takes Gramsci’s famous dictum as a starting point to understand the twin, opposing , potentials of left and right populism out of the current global impasse typified by Trump, and Brexit. One of the first of a very welcome new pamphlets series from Verso short enough to be read between canvassing sessions to the point, intelligent writing leaving campaigners wanting more

For the ‘new to be born’ demands that the ‘old’ has to be subject to critique, Stephen Duncombe describes this process as ‘reimagining politics’ which he explains in a new edition of his superb 2007 book Dream or Nightmare updated to take in the age of Trump. Such a reimagining demands an engagement with what politics means for those whose entry post-dates the 2008 financial crisis, 2019’s first and second time voters on whose support Labour is counting so much. Keir Milburn’s Generation Left should be considered the set text for such connecting with these voters’ practical ideals , this is meant as a compliment richly deserved, by the way.

And after the votes have been counted, what changes and how much? The annual Socialist Register has taken for its 2020 theme ‘new ways of living’ with an admirably global view of the cusp new vs old. A scary vision of how such a transition might end up is provided by Peter Fleming’s The Worst is Yet To Come described as a post-capitalist survival guide, ranging over economic decline, societal division and environmental detonation. Oh well, it wasn’t good while it lasted. To prevent such a vision becomes a reality requires a conversational culture that enables differences of opinion to be shared rather than as a badge of rising intolerance. Two contrasting approaches to this are provided by Billy Bragg aad Richard Seymour, yet both take a similar starting point, social media. Billy’s The Three Dimensions of Freedom champions democratisation in the face of what some have described as ‘surveillance capitalism’. While in The Twittering Storm Richard tackles the degradation of political debate the entire social media edifice has helped bring about. In time honoured fashion we need both, institutional change and taking personal responsibility to effect that change. The importance of both approaches cannot be underestimated with elections increasingly fought as much online as on the doorstep.

Even in the heat of the such campaigns we need to locate change, personal and political, in the midst of what theorists call ‘the conjunctural’, the terrain of the present. A special edition of the journal New Formations takes this as its theme This Conjuncture drawing on the work of Stuart Hall to apply the theory to a wide range of what constitutes the present.

Of course any sense of this particular ‘conjuncture’ is pretty much defined by all things Brexit. But of course the issue and what it raises has a history too. Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson’s Rule Britannia : Brexit and the End of Empire makes this precise point very well, imperial nostalgia a powerful political mobiliser, still. In The People’s Flag and the Union Jack Gerry Hassan and Eric Shaw apply the consequences of an Englishness entwined with the imperial and the martial to the enduring failure for Labour to engage with either the break-up of Britain or the consequent re-emergence of the English nation. Both are of course vital to any understanding of Brexit.

It isn’t however a crude reductionism though to suggest that Brexit must also be understood via the prism of class. Mike Carter’s All Together Now? is an epic journey of walking half the length of England to help provide that prism, the deindustrialised communities almost entirely disconnected from the body politic, what kind of answer are the parties providing to their howls of rage? In a similar vein Our City by Jon Bloomfield is a incredibly powerful testimony of how race and migration shapes the modern British city, in this case Birmingham, establishing grounds for both unity and division, the choice of which is entirely political. Riding for Deliveroo the debut book from Callum Cant is another potent rejoinder to those who would reduce the entire General Election to all things Brexit. Callum’s spirited case for a resistance to the the ‘new economy’ should be mote than sufficient to convince it shouldn’t be.

If an election shaped by the Brexit Impasse fails to respond to these many and varied howls of rage the future will be anything but progressive. Cas Mudde’s The Far Right Today connects such an understanding to Brexit’s transatlantic equivalent , the 2016 triumph of Trumpism. A triumph framed by a populist racism coupled with authoritarian populism that has its origins in, and message projected by the alt-right. The New Authoritarians by David Renton is an important, new, analysis of this phenomenon that distinguishes this radicalised, racist right from more traditional versions of classic fascism. All the more dangerous for this shift. As David argues, our opposition and offering of alternatives is strengthened not weakened by understanding the nature and appeal of what we are up against. Casting votes will be not enough.

The biggest issue in the election surely should be the Climate Emergency. This will be the shape of politics to come so its useful to have a handbook for these decades to come whoever is in government. None better than Paul Mason’s latest, Clear Bright Future a guide to past and present crises beyond any conventional electoral focus and a map of what a radical future in their place might look like too. A more conventional response is provided by System Change not Climate Change edited by Martin Empson. Conventional in the sense that most of the contributors derive their politics from Marxism. It is not to deride the entire legacy of this most revolutionary of ideologies to recognise that firstly its contribution to our understanding of the environmental crisis is negligible, and secondly other, revolutionary, ideas are serving to not only make up for that absence but inspiring millions to action. A combination superbly personified by Greta Thunberg. Greta’s short book No One is Too Small to Make A Difference would be my pick as the perfect 2019 Manifesto . And as for a campaign guide, Extinction Rebellion’s handbook This is Not A Drill showcases the scale of audacity, action and creative resistance this campaign has generated in such a short time. But however imaginative, however creative, in the same way that voting is not enough nor will blocking roads be sufficient if the Climate Emergency is to be reversed. We need ideas that become policies and in turn become government action. Labour putting a Green Industrial Revolution at the centre of its message is a hugely important development in this regard, tho’ Katherine Trebeck and Jeremy Williams’ The Economics of Arrival indicate how far traditional, including left, governments needs to travel to produce a society that is sustainable.

Despite the claims of politicians on the stump in politics nothing is ever entirely ‘new’. It pays to take more than a moment to pay heed to the past. Portugal ’74 is one such instance, the most potent example yet of revolutionary change where we’ve become accustomed to least expect it, Western Europe. An episode brilliantly recalled by Raquel Varela’s new account, A People’s History of the Portuguese Revolution . Closer to home the new edition of Rebel Footprints by David Rosenberg is a guide the streets and other parts of London that carry with them a radical past. A history lesson on the move, what a way once those canvassing sessions are over to spend a Sunday afternoon after 12th December, with David’s book in hand, strolling for socialism. Anti-racism is a strand that runs through much of this past, or at least it should. Evan Smith’s history British Communism and the Politics of Race may focus on one particular part of the Let and its changing relationship to anti-racism, yet the insights provide a much broader perspective on what makes, and what doesn’t, an anti-racist Labour Party. To keep up to date (sic) more broadly with the historiography of communism there’s no better source than the journal Twentieth Century Communism, the latest issue testament to its customary eclectic mix, Eric Hobsbawm, the Brothers Grimm and the Communist Party of Cyprus.

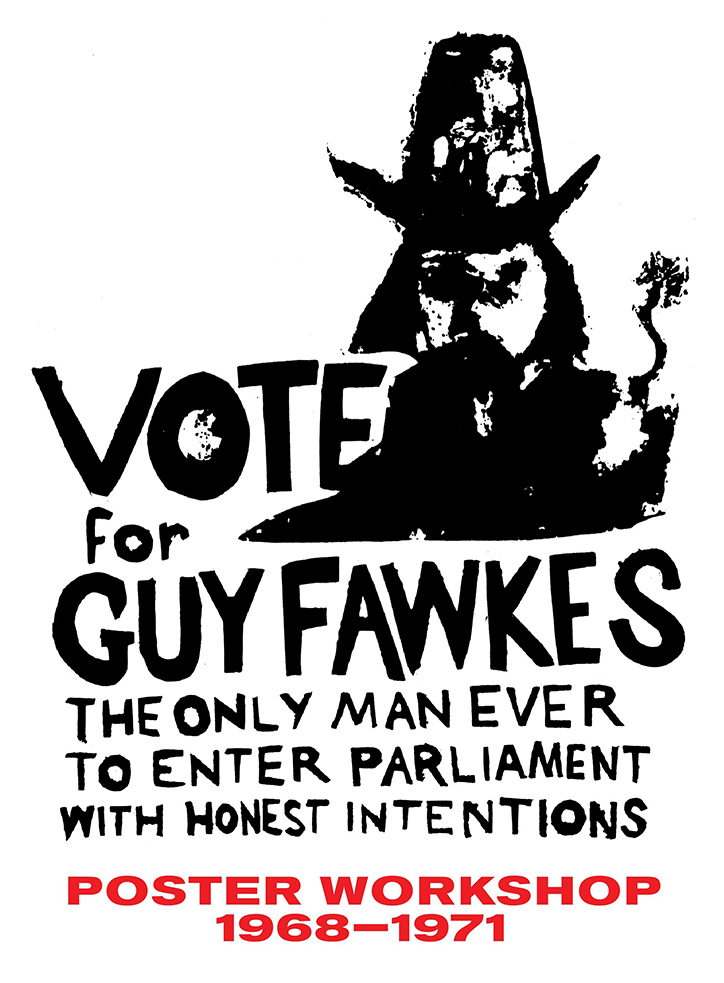

A range of new titles offer an impressive revisiting of how to construct a political culture. Too little has been done on this front by Labour since Jeremy Corbyn became leader. In the rush and tumble of the campaign theres’s Fck Boris and Grime4Corbyn but what will remain of this after the polling statins close? If ’17 is anything to go by, not a lot. Beautifully produced the songbook Working Class Heroes : A History of Struggle in Song edited by Mat Callahan and Yvonne Moore provides like-minded artefacts from the past to inspire us towards what the life and soul of the party. but look, and sound like and the beauty of this book is that with instrument in hand the musical notation can be turned into a weapon of change here and now. Visual Dissent is an extraordinarily vivid collected works from the much-celebrated photomontage artist Peter Kennard, if only more of the Left took note of Peter’s ability to communicate with wit, humour and impact. The LGBT movement is never backward at coming forward with communicating its hopes, ambitions, demands for change . The origins of that political, and cultural imperative are beautifully chronicled in the photos and accompanying essays from Stonewall ’69 which comprise Fred W. McDarrah’s Pride : Photographs after Stonewall. And as for a soundtrack? In Don’t Look Back in Anger Daniel Rachel chronicles the rise and fall of Cool Britannia, a music, that just like the politics of the same era, the 1990s and noughties, that promised so much but in the end didn’t live up to. Better luck this time, eh?

And as for when the cut n thrust of the campaign serves to get a tad blunt and tawdry I recommend a turn to How to be a Vegan and Keep your Friends from Annie Nichols. Individual, lifestyle choices aren’t be sufficient in themselves, we need a governments to effect change on the scale the Climate Emergency requires yet reinventing our diet and ‘keeping our friends’ provides mote than an inkling of both what is possible and necessary. Tasty too. Who knows what the future might hold after 12th December , we can but dream, with many sacrificing evenings and weekends to help make it happen. A very welcome return therefore of the Big Red Diary to help plan the first year of supporting, resisting, or maybe even a mix of the two, a new government.

And my book of the General Election campaign? Matt Abbott’s debut poetry collection A Hurricane in my Head : Poems for When Your Phone Dies. Poetry? And these are for children too?! What’s that got to do with 12th December, eh? Heaps. This is a once-in-a-generation vote, not only to determine Britain’s relationship with Europe via the EU but also the scale of ambition to tackle the Climate Emergency. On both fronts those of us of a certain age will struggle on, learn to live with the dire consequences if the worst possible result imaginable materialises and Johnson is back at Number Ten come the morning of 13th December. But those at secondary school, the age Matt’s book is primarily aimed at, will have to live with the fallout for their adolescence. A Johnson victory moreover will cement the popular shift to the Right, institutionalise its grip on power for a considerable time to come, those at school now facing the grimmest possible future. At the very moment the Climate Emergency needs reversing most urgently the least will be being done to stop it. The school climate strikers symbolise an entirely different discourse, hope on the move, pinning the blame for the dire prospects for their future squarely on those old enough to know better. Hope, and Matt’s poems capture this potential superbly with a line in humour that the grown-ups will smile along to warmly. 12th December, for those not yet old enough to vote is just the beginning and this is their book.

Note No links in this review are to Amazon, if you can avoid buying from the corporate tax-dodgers please do.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction,’ aka Philosophy Football.

What Do They Know Of Cricket

19.07.2019

England’s Cricket World Cup Win has Philosophy Football's Mark Perryman hunting out his favourite CLR James quote to make sense of it all

Illustration Hugh Tisdale / Philosophy Football

Cricket’s version of the ‘years of hurt’, 44 in this case, came to a spectacular end early Sunday 14th July. Thrilling, eventful, and glorious, no wonder the front pages the following morning were full of it, the sub-editor who came up with the headline ‘ Champagne Super Over’ surely in line for a hefty bonus.

What does a World Cup Win mean, a concocted, nationalistic, distraction? Or hip-hip-hooray the world has changed at the flick of a super over and superior number of boundaries, the nation will take up bat and ball, obesity crisis, what crisis? The truth lies somewhere in-between, or as CLR James famously put it ‘ What do they know of cricket who only cricket know.’

The hoo-hah over the tournament’s TV broadcasting rights sold off to the highest bidder, aka a Sky TV subscription channel, illustrates this perfectly. The Women’s Football World Cup campaign of England, and Scotland, attracted record-breaking viewing figures, in their millions, over 12 million for England’s semi-final. In contrast until the Cricket World Cup final, after much pressure shared with Channel 4, the tournament scraped by on a few hundred thousand viewers. The difference couldn’t be more obvious, ever since the birth of satellite TV hyped up claims have been made about the virtue of its generous purchase of TV rights, yet in every single case those following the sport on TV have plummeted, popular interest squandered, and the largesse wasted. And of course participation levels declined. Why on earth would any host nation allow a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a domestic World Cup be squandered in this way? Yet this summer we have not one but two examples, Cricket and Netball. The latter wasting the biggest chance it has ever had to grow a sport virtually every woman in this country has played during their schooldays. A sport the overwhelming majority promptly give up when walking out the school gates for the last time, never to return to the netball court. There’s been a modest reversal of this depressing trend following England’s Commonwealth Games Gold Medal but nothing like on the scale of platform a World Cup offers. But like the cricket not if it’s watched by a fraction of the numbers terrestrial TV would have attracted.

These sports’ governing bodies, and there are plenty of other examples, clearly cannot be trusted with the wider interests they are charged with. Of course most, though by no means all, are hard-pressed for funds, but when participation is sacrificed for short term injection of cash then something is clearly amiss. Some, not enough, sporting events broadcasting rights are regulated, made unavailable to the satellite channels, only to be broadcast on terrestrial. As a first step an incoming Labour government should significantly extend that list, any domestic World Cup or World Championship for starters, the Ashes too . Nanny state? No, standing up for the nation’s sporting interests.

Those interests are centred on two roles sport performs like none other. Encouraging participation and framing a common-sense nationhood. On the same weekend as that epic World Cup final terrestrial TV also treated us to the Wimbledon Finals and the British Grand Prix. Both attracted huge audiences but neither will lead to many, if any, taking up driving round Silverstone as a hobby and not a lot more picking up racquet and ball either. That is because participation isn’t just about what we can watch on TV from the comfort of our own sofa, it is about providing the means to get us off that sofa too. Sport is socially constructed, a local go-kart track for the child inspired by Lewis Hamilton’s 100mph derring-do might do for starters yet the numbers who can afford to enter this hugely expensive sport at a competitive level are minuscule. And tennis? The annual platform Wimbledon provides tennis frames it as an intensely upper middle-class pursuit, from the Royal Box guest list to strawberries and cream followed by a glass of Pimms. A revolutionary reinvention of tennis would see it become an urban, inner-city sport. A concrete tennis court is not only vandal-proof it requires zero maintenance. An army of local authority coaches providing the much-needed structure to encourage those who pick up racquet and ball. The focus on sport as mass participation, for the many, ring any bells? Any few who make it up the ranks to play at Wimbledon a pleasant surprise not the sum of our ambition. Having regulated the broadcasting rights an incoming Labour Government should also run an audit of every sports governing body’s finances, any failing to meet toughened participation objectives deprived of the generous state support they receive. Totalitarian? No not all, as most fans and grassroots participants would agree these sports have lost the right to be trusted.

Participation in physical activity is key to the nation’s health, but sport is even bigger than that. A World Cup, of any sport, reaches the parts of a sporting nation like nothing else. When Liverpool won the Champions League the blue half of Merseyside looked away with studied indifference while they were hardly dancing in the streets of Manchester, North London and elsewhere either. A World Cup win is of a different scale. Mobilising the casual observer to become a hardened fan for a month at least, or in Eric Hobsbawm’s brilliant phrase ‘ An imagined community of millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people.’ But of course that ‘imagined community’ is hugely contested, never more so than in this era of the Brexit impasse. Jacob Rees-Mogg clearly hadn’t spent very long on the playing fields of Eton if he could in all seriousness tweet in the immediate aftermath of England’s World Cup victory, ‘We clearly don't need Europe to win.’ Nothing reveals faux-populism like a politician’s ignorance of sport. This was an England team with an Irish-born captain, an opening batsman born in South Africa, a man of the match born in New Zealand, wicket takers born in Barbados and the grandson of a Pakistani immigrant. Diverse, multicultural, and all the better for it. Of course this isn’t enough to roll back a resurgent popular racism but it’s a start, an unrivalled platform for a very different imagined nation to the one of Rees-Mogg’s imagination.

What do they know of cricket who only cricket know? Not enough, without an understanding of the social impact and construction of the kind of national conversation English cricket's World Cup win is incomplete. But what CLR James also taught us is that sport matters for it’s own sake too, not as a deviation from the real world but for millions an invaluable part of that world too. England (and Wales) savouring that moment of victory, without apologies, in this instance changing the world will have to wait ‘til another day.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football, our World Champions T-shirt celebrating the diverse , multicultural England Team is available from here

Liberté, Egalité, Velocité

06.07.2019

Juillet, the month of Le Tour and Bastille Day too . Mark Perryman offers up a 5-point transitional programme for a cycling revolution

July, the month when since 2012 first Wiggins, then Froome, last year Thomas turn Le Maillot Jaune into Le Maillot Britannique. Or in Thomas’ case Le Maillot Gallois. And off the back of this a surge in riding our bicycles rather than simply watching the excellent TV coverage on ITV4, or not. According to the latest figures Department for Transport’s figures only 6% of the UK population cycle at least once a month, just 1% of primary school children cycle to school, a mere 3% of secondary school children, and compared to Europe we remain the third lowest of daily cyclists, at 4%, only Cyprus (2%) and Malta (1%) get on their bikes less than the Brits.

Once again the myth that elite success, Le Tour, Team GB’s hatful of gold medals in the Olympic Velodrome, the cycling world championships coming to Yorkshire in the autumn, is proved to have next to no impact on increasing participation. Yet cycling not only helps generate a healthier population by getting us out of our cars (the same data revealed that the average length of a car journey is 8.5 miles) we can help alleviate urban air pollution, reduce reliance on fossil fuels and decarbonise the economy. Le Maillot Jaune won’t achieve any of this, La Révolution might. It was Trotsky who once offered up a ‘transitional programme’ from capitalism to socialism, mine is a tad more modest from four wheels, to two.

1. No VAT on Bikes

A signature move would be to remove VAT on bicycles. A 20% reduction across the board on the price of a bike, anything from £200 upwards, isn’t to be sniffed at, and uses tax gathering as a tool to actively shape lifestyles. Something that will be required more and more by any government seriously committed to a sustainable economic strategy.

2. Socially Useful Bicycle Production

In the past few years there has been a spate of car factory closures. This is unlikely to slow down, consumer habits are changing, sadly its not that car-drivers are driving less, it’s that they’re driving existing models for longer. The urgent need to upgrade every couple of years is coming to an end. And electricity is coming to replace the petrol in the tank. Good, but where does the electricity come from? If not renewables while pollution may be reduced, the impact on climate change much less so (same applies to E-bikes). Those factories could be taken over by the state. Used to churn out cheap but well-made bikes. Rather than front-wheel suspension, which is entirely unnecessary for the vast majority of journeys. Lightweight steel is what improves the quality of any ride. Focus on this for a line of nationalised, not-for profit children’s and adults’ bikes. Those centres of car manufacture are unlikely ever to recover, certainly not on the scale they once had, but what if they became centres of bike manufacture?

3. Bicycles on trains

Eight and a half miles isn’t a bad standard to aim at. Of course many car journeys are considerably less, there’s no need to aspire to Le Tour standards straightaway. Most of us, depending on any hills getting in the way, could do those 8.5 miles in well under an hour. In big cities that will be quicker than by bus, and no wait for the next train either. But for some the journey to work is considerably longer. Why then does commuting by train actively discriminate against those who’d take a bike to complete the journey? The only ones permitted the expensive ‘2ndbike’ option, the fold-away. And at the weekends its no better, a ride in the country for city-dwellers made all the more difficult because the train ride to get there has next to no space for bikes. None of this applies on the continent where it is not uncommon to find entire carriages given over to cyclists and their bikes. What new train design in the UK has even begun to address this? The answer is the total opposite with ever-decreasing provision for carrying bikes, madness, both commercially and for the environment.

4. A bike shed for every workplace

OK, 8.5 miles is going to leave most of us a tad sweaty. If of the all-weather cycling variety quite possibly soaking wet and caked in mud too. No way to start the working day. Every workplace needs to be kitted out with a bike shed, changing room, showers. Central and local government should set the example in their offices, but tokenism isn’t enough. Instil this in planning regulations for new workplace builds, interest-free grants for all existing workplaces to add this provision.

5. The cyclists’ road to socialism

In the early years of socialism ‘Clarion Clubs’ of socialist cyclists would take body, soul and the message for change from city to countryside. A late 1980s version was the annual Oxford to London Nicaragua Solidarity bike ride that thousands would take part in every year. Despite the supposed frailty of Jeremy Corbyn being challenged by pictures of his regular Islington to Westminster, 4.5 miles according to my road map, cycle-commute, it is a culture largely absent from the Left nowadays. Yet mass cycling has the potential to provide the means and confidence to generate the day-to-day ride as a matter of course. Such events are hugely popular, organised by commercial outfits for the major charities. But these re nothing more than a day out, entirely disconnected to any ambition to transform the way we live our lives and consume the world’s ever-decreasing resources. A left cycling culture could help generate instead what the writer Lynne Segal has described as moments of ‘collective joy’ a day out yes, but with a world, not just a wheel, to change too.

I could add of course safer cycle ways and paths. These are certainly needed, fear remains a major impediment to the revolutionary growth in cycling to our individual and collective benefit I am advocating. Yet the overwhelming emphasis on this, to little or no substantial change, serves only to produce a self-fulfilling prophecy. If it’s that dangerous, which it isn’t, and nothing is being done about it, which it hasn’t, why bother? Like any decent manifesto for a revolution mine is the advocacy therefore of hope, not despair.

Liberté? Yes. Egalité? Of course. Velocité? Why not. Driven not by profit or an economic system driving our planet to destruction but by ourselves. A Révolution in anybody’s language.

Mark Perryman is an active cyclist and co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football. Out just in time for Le Tour our Liberté, Egalité, Velocité T-shirt is available from here.

The Never-Ending Season

14.05.19

As one sport’s contest approach its climax another has barely begun Philosophy Football’s Mark Perryman reviews summer books for those who measure their years out in seasons not months.

The summer beckons. The Carabao, or those of us a tad old skool, League Cup Final is long gone. The FA Cup in association with wotsit airlines has had its Final too, ditto the Champions and Rich Runners Up league too. Up and down the divisions clubs have jostled their way to win promotion, staved off relegation or clung on to mid-table mediocrity. And for the few, not the many, the Premier League title. Before you know it, all this will be done n’ dusted ready for it to begin all over again, the 2019/20 edition. What better time therefore to reflect on the modern meaning of our much-fabled People’s Game? For a comic-strip insight mixing fine art with bittersweet commentary there’s none better than David Squires. David’s strips, 2014-2018 handily now collected in one very tasty volume Goalless Draws. Stuart Roy Clarke likewise takes a visual approach to locating the lost meaning of football, this time tho’ via a photography that he has made his own under the rubric ‘homes of football’. Stuart’s latest collection The Game combines the finest photographic record of the changes in football, with a superb accompanying text from the one of the founders of football’s academia, John Williams. Together they make for a superlative double act. Part of Stuart and John’s argument, and the appeal of their book, is that there really is no substitute for ‘being there’. This is an experience that has changed markedly since the ’89 Hilsborough tragedy, a moment caught most poignantly by David Cain’s book-length poem Truth Street. For the most part those changes have been for the better but no one can pretend that ‘being there’ is the same any more as it once was. A point expertly made by Duncan Hamilton in his new book Going to the Match a journey to games which confirms that despite all the worst efforts of corporate homogeneity the proverbial wind and the rain of 90 plus minutes in the stands cannot be beaten. What the modern ‘matchday experience’ (ugh!) has become is the effort to convert our fandom from active participants to passive consumers. Dave Roberts is having none of that in Home and Away he travels round non-league football to find a game largely untouched by the trappings of what has become disapprovingly known as ‘Mod£rn Football.’

For those who can afford the time, and the expense (though with a bit of careful pre-planning these trips can be surprisingly cheap) another way of escaping how our domestic game is consumed can be via a European away weekend. For an excellent starting point towards choosing such a trip read Neil Frederik Jensen’s Mittel and discover the appeal of heading off to see a game in Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and elsewhere. A more familiar trip would of course be to La Liga or the Bundesliga. For the former pack a copy of Jonathan Wilson’s latest, The Barcelona Legacy in which Jonathan provides his now customary digest of tactics to better understand the game unfolding before our eyes. And for Germany, take with you Uli Hesse’s Building the Yellow Wall for a superb account of this most idiosyncratic of clubs, not least because this was where Jurgen Klopp learnt his managerial trade and Jadon Sancho is currently building his formidable playing career. But of course the biggest, and proved to be the best, away trip of the past twelve months has to be the one those lucky England fans made to World Cup 2018, bringing home England’s first World Cup semi-final appearance in 28 years for their troubles. In How Football (Nearly) Came Home Barney Ronay tells the full, and unforgettable story of that glorious English summer of football, if the wait is as long as it was from the previous one at least we’ll have a classic read that stands comparison with Italia 90’s All Played Out by Pete Davies to savour in the meantime. Of course some football destinations are more welcoming than others. That’s not to say fans shouldn’t take the risk of being pleasantly surprised. Andrew Hodges helps readers towards that happy outcome by unpicking the more complex reality behind the fearsome reputation of Croatian football in Fan Activism, Protest and Politics: Ultras in Post-Socialist Croatia.

Closer to home Michael Calvin has an unrivalled reputation for chronicling football’s pluses, and all too many minuses, via a series of award-winning books. His latest State of Play ranges over stories of players, managers and clubs to create the kind picture of English football that rarely makes it on to the back pages yet is way more important than who scored what against whom. Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg’s The Club doesn’t have much doubt what has caused the perversion of the sport, the unseemly wealth and disruptive influence of The Premier League.

The latest edition of Soccernomics by Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski provides a highly accessible, and entertaining, framework to understand the Premier League’s evolution. Or for an unashamedly radical deconstruction of the entire edifice Gabriel Kuhn’s Soccer vs The State, also now available in a new edition, should satisfy all who harbour such an ambition. If on the other hand the preference is for an alternative universe of football then David Wardale’s Wasting Your Wildcard is a hugely entertaining , not to mention indispensable, guide to that mid 1990s throwback, Fantasy Football, and I add that historical footnote writing as the co-founder of another football-inclined mid-1990s throwback!

Football, fantasy, philosophy, Mod£rn or any other version has of course become an almost entirely sedentary pastime. A national obsession divorced from any kind of desire to physically partake in it as a sport. Football more than any other sport demolishes the role model / emulation model. If the Premier League or an England World Cup run can’t get the nation off our sofas what hope for any other sport? The exception, for a while at least, has been cycling. Although of late even this seems to have levelled off at best, or more likely declined. Cycling’s temporary success in boosting numbers on two wheels coincided with unprecedented British cyclists’ success at both the Olympics and Le Tour. How to Ride a Bike by Chris Hoy handily combines both, all the glamour of a six-time Olympic Gold Medallist with a how-to-guide for those who’d like to cycle both further and faster.

Unfortunately, however closely we follow Chris’s helpful hints only a tiny minority of us will ever reach the kind of speed, uphill and downhill, catalogued in The Cycling Podcast by Richard Moore, Lionel Birnie and Daniel Friebe who are as much a joy to read as their podcast was to listen to. Of course there’s not much doubt what was the highlight of cycling’s 2018, Geraint Thomas surprising everybody, not least himself by winning Le Tour, a story he retells in his own inimitable way The Tour According to G

Meanwhile for those of who still hanker after two-wheeled speed and endurance Peter Cossins has written the near perfect book Full Gas in which Peter seeks to instruct mere mortals in the tactics of the peloton. If we cannot dream, well what exactly is the point of doing, or watching sport?

As the sporting summer fast approaches there’s plenty of contenders for the stand out event. A home cricket world cup? The women’s football world cup? The debut of the UEFA nations leagues semis and final. Another home world cup, netball? In years gone by an Ashes summer would have seen off the lot of them but not anymore since the disastrous decision to sell live and free-to-watch test cricket to the satellite TV moneymen. And cricket has its own problems as a sport too, Australia’s fall from grace via a ball tampering scandal brilliantly chronicled by Geoff Lemon in his Steve Smith’s Men.

And then there’s the Rugby World Cup in the autumn to look forward to. A first, hosted by Japan, instead of one of the ‘traditional’ rugby nations, however the sport’s globalisation, like cricket’s, remains faltering at best. A world cup model adopted to ape football for commercial, reasons but lacking any cultural ambition to truly spread the game. Perhaps rugby’s bigwigs should read Stuart Barnes’ full-on rugby memoir Sketches from Memory to remind themselves of what the sport at its best has to offer the world.

Golf has its own version of globalisation, the Ryder Cup surely the only sporting event with a team competing under the EU flag, but what will happen with GB golfers in Europe’s side flying that flag post-brexit? Tiger Woods is the one golfer of the current era to reach beyond the sport’s core support to spur some kind of revival of interest, his April 2019 win at the Masters absolute testament to that. A hugely talented but much troubled figure Jeff Benedict and Armen Keteyian’s unauthorised biography Tiger Woods helps untangle the reason for why Tiger is, and remains, a figure who towers above his sport..

Wimbledon fortnight provides a sudden burst of interest in tennis. Apart from that it’s down there with the also-rans. Gregory Howe’s Chasing Points is a welcome insight therefore into the pro-tennis tour as players scramble points to climb up the rankings. A revelation, it helps to put the world of All England’s SW wotsit into some kind of perspective.

But for a sport on the up, look no further than darts. The rise and rise hilariously chronicled by the always brilliant Ned Boulting in his new book Heart of Dart-Ness. Bullseyes, the pub game, a packed Ally Pally, world champions, and those garish shirts, Ned’s book has the lot, and then some

Darts is a sport just about anyone can play. OK there might not be as many pubs with a handy dartboard as there once were but this kind of accessibility still provides darts with its instant appeal, to take part. Too many sports don’t have that whilst others despite the appeal of so-called ‘role models’ never had it in the first place. Helen Croydon’s This Girl Ran provides the kind of inspiration, in shedloads rather than the odd spoonful, to get off our collective sofa and enjoy the doing , rather than the watching, of sport. Helen’s tale takes this to extremes, the triathlon, but the maxim remains pertinent, we can all run. Bump, Bike & Baby by Moire O’Sullivan takes this how-to philosophy to another level, combining pregnancy, parenthood and ultra-endurance adventure racing. Remarkably she proves the combination is not only possible but desirable. The latter may not be the response of too many readers but the very fact that Moira survives to tell her tale could just prove sufficient inspiration for others to follow in her footsteps, just not quite as many.

Of course, most won’t. This has precious little to do with individual choices, rather it is down to the social construction of sport. Vikki Krane’s Sex, Gender and Sexuality in Sport is as near as we’re ever likely to get to a comprehensive analysis of just one dimension of the exclusions sport both produces and reproduces. There are, unfortunately, plenty more. Despite this, it is rare indeed to find any kind of politics that takes this seriously. Gabriel Kuhn has done an excellent job, therefore, rediscovering and translating from the 1930’s Julius Deutsch’s writings Antifascism, Sports, Sobriety for a model of the possible.

But one writer, and political activist, above all others effortlessly made the connections that others either struggle with, or dismiss entirely. In his classic work Beyond a Boundary, pan-african, marxist and cricket-lover CLR James asks the rhetorical question ‘ What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?’ The same question could be asked, and answered for each and every other sport too. My pick of the quarter therefore is Marxism, Colonialism and Cricket. No, not your common or garden title for the most outstanding sports book of 2019, to date, perhaps that’s the problem? But what the editors David Featherstone, Chistopher Gair, Christian Høgsberg and Andrew Smith have achieved is truly special mixing James’ personal and political lifestory, the context of cricket in the West Indies, the past, present and future of cricket writing. Superb, just the read whilst that old imperial encounter, The Ashes, seeks to nudge the Premier League’s off season from the back pages this sporting summer.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football.

The Making of a Two Tone Nation

09.03.2019

40 years on Mark Perryman celebrates the debut release from The Specials

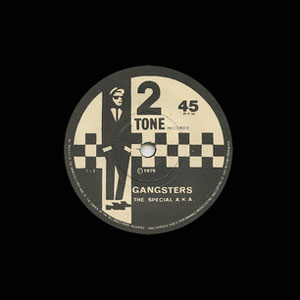

03.05.1979 Margaret Thatcher leads the Tories to a crushing General Election defeat of Labour. The next morning I pop into the small independent record shop tucked away by the platforms at Hull railway station to pick up the eagerly awaited debut single by The Specials, a double A-side with label mates The Selecter on the reverse. What an antidote.

For the preceding couple of years the National Front had threatened both a street-fighting and electoral breakthrough. The Anti Nazi League (ANL) mobilised in opposition everywhere they appeared to challenge the fascists’ ability to organise. The investigative magazine Searchlight exposed via fearless intelligence-gathering the neo-nazi origins of the NF’s leadership and key organisers. And most imaginatively of all Rock against Racism (RAR) via a mix of huge carnivals and local gigs had spread the message that the NF stood for ‘No Fun, No Freedom, No Future’ to drive a wedge between punk and its nihilistic appeal and the NF. Punk’s flirtation with the faux-shock value of the swastika and Nazi chic had until this kind of intervention all the potential to provide a useful base of support for the NF.

A fortnight before polling day the ANL had organised a massive protest outside an NF election rally provocatively sited in multicultural Southall and to be addressed by their wannabe Führer-in-Waiting, John Tyndall. The counter-demo was brutally policed by the notorious Special Patrol Group, so brutal that their actions resulted in the death of one demonstrator, Blair Peach.

The late 1970s were these kinds of dangerous times. When the ’79 General Election votes were counted the NF had been humiliated at the Ballot Box. Despite standing in seats from Accrington to York and most places in-between they barely topped 1% of the vote in these contests nationwide. Their best single result still only a measly 7.6% for Tyndall in Hackney South and Shoreditch. But the NF’s setback, however welcome, was less down to the reversal of their racism than its embrace by the more mainstream, Tory, right.

In January 1978 Thatcher had said in a set piece World in Action TV interview of immigration:

“By the end of the century there would be four million people of the new Commonwealth or Pakistan here. Now, that is an awful lot and I think it means that people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture and, you know, the British character has done so much for democracy, for law and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in.”

Despite her qualifying these remarks elsewhere in the televised conversation the message was perfectly clear, Vote Conservative, stop the ‘swamping’ of ‘our’ culture, no need to vote NF because the Tories would be doing their job for them.

The Specials stood for an entirely different version of ‘this country’ to Thatcher’s. A 2 Tone nation celebrated via riotous gigs, frantic dancing, mixing up the anarchic energy of post punk with the original sound of Jamaica’s Prince Buster, Desmond Dekker, Harry J Allstars and others. Dressed up to the nines in tonic suits, loafers, button down collar shirts. A musical movement rooted in the hugely contradictory sub-culture of skinheads. Rocking against racism no longer simply a prescription rather the natural consequence of the sounds we loved, the multicultural places where Ska was being reinvented, Birmingham, Coventry and North London in particular, the bands we followed up and down the motorways to all points north, south, east and west.

Hull was as much affected by all this as anywhere else. The SWP had a bookshop on Spring Bank that had become pretty much the hub for a thriving local Rock against Racism scene. The Wellington Club, affectionately known as ‘The Welly’ to all who frequented it was a hotbed of punk, indy and post-punk. Both helped pull together a mainly young crowd who would fill coaches to stop the NF and British Movement wherever they threatened to march. One memorable excursion of this sort to protest against the Far Right’s favourite racist landlord, Robert Relf, then languishing in Winchester prison, left Hull past midnight so the music crowd could see Howard Devoto’s Magazine gig at the local FE College too. There was an uglier side to this mix tho’, pubs to avoid because they were well-known NF hangouts, a visit to the toilets there likely to end in a bloodied confrontation, they firebombed the bookshop too. Ska helped however mould the activism and the music into some sort of movement. The coolest kid in these parts was Roland, a diehard Clash fan, mixed race with a blonde rinse his nickname, before any of us knew any better, was ‘Guinness’ . His mum ran a second hand clothes shop, if we wanted the sixties ska look on the cheap her’s was the place to find a vintage bargain. And when Roland formed a ska band, The Akrilykz, it was the Communist Party who provided the lead guitar and drummer. Now that’s what I call a Popular Front. But it was on lead vocals that Roland provided a mesmerising presence, despite his moniker, personifying everything we believed in. His quietly understated voice soaring with the breathless melodies that a few years later he, Roland Gift, would bring to the Fine Young Cannibals.

Hull, up and down the country, on the road, 2 Tone and it’s offshoots rapidly became this kind of movement everywhere. Not in the conventional political sense, nor the gloriously disorganised effectiveness of RAR’s self-styled Militant Entertainment either. When the first Two Tone Tour reached Sheffield I joined it on a minibus from Hull. The dancehall was heaving, on the cusp of some kind of musical rebellion, threatening yet joyful at the same time. The notorious South Yorkshire police however suspected something untoward was afoot and tried to close the gig down. I’ll never forget Specials lead singer Terry Hall’s response. He bounded on stage, asked us all to sit down on the dancefloor and then to the senior police officer’s face led the entire audience in chorus after chorus of the ‘Harry Roberts Song’. Grudgingly, and knowing the alternative was likely to be a seriously wrecked venue in the face of this the police didn’t have much choice than allow the gig to proceed. 1-0 to 2 Tone.

Another unforgettable ’79 night was spent at Camden’s tiny Dingwalls nightclub. It was the evening of the first performance of Madness on Top of the Pops and to reward their loyal fans the band were playing live straight afters. I was one of the lucky few crammed in, packed shoulder to shoulder with British Movement skinheads. This was genuinely scary, my hair was short enough to pass muster, my politics certainly not. It was one of the contradictions of 2 Tone, and the original ska numbers too, a sound imported from Jamaica, reinvented by inner-city England, embraced and danced to by some, at least, who were avowedly racist. But of course, for the most part not. Messy, violent even, on occasion, the irresistible beat of 2 Tone most belonged to a predominantly working-class fan base who fancied a good time while having the common sense to leave any racism they might be bringing along to the show at the door. In this way music like most aspects of popular culture is a staging post towards social change rather than the vehicle for it. We ignore the potential of the former at our political peril, but try to enforce it into becoming the latter and we starve the music of it’s originality and dynamism. That’s not to say the bands weren’t political, The Specials having topped the charts in ’81 with their epic Ghost Town headlined the Leeds Rock against Racism carnival, which ended up being the last UK live performance of the original line-up. While label mates The Beat’s Stand Down Margaret was the definitive anti-Tory dance number for a generation.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the breakthrough of 2 Tone didn’t exist in a vacuum. Thatcher’s elevation of a racist discourse around ‘swamping’ was followed by the raw nationalist-populism of the Falkands War and an increasingly punitive law and order agenda. The street-fighting Fascist Right remained an ever present threat. The mix was toxic but ska, The Specials most of all, did at least provide the national anthems for a 2 Tone nation in the making. In the era of Thatcherism this seemed like another country. But no, it was ours, and that other lot despite their worst efforts could never take it from us.

All illustrations by graphic designer Hugh Tisdale co-founder of Philosophy Football and available as T-shirts from here

Mark Perryman is the author of The Corbyn Effect his new bookCorbynism from Below is published in September by Lawrence & Wishart.

A New Year Armoury of Reading

27.12.18

Armed with optimism Mark Perryman makes a selection of the books he'll be depending on in 2019's battle of ideas

Not much doubt which argument will rage on long after any Christmastime peace and goodwill has disappeared, Brexit. Fintan O’Toole’s Heroic Failure is an account of this most dismal of sagas which locates its gestation in a mix of imperial delusion and cultural confusion rather than this deal, that deal or no deal. On a similar front England’s Discontents by Mike Wayne is an exploration of English national identity that provides a highly effective insight towards understanding the politucal terrain of post-Brexit Britain. Any such process will revolve around competing definitions of ‘control’ and precisely who, or what, we need to take it back from. Gianpaolo Baiocchi’s We, The Sovereign describes models of sovereignty that retain both an egalitarian impulse and the power to transform. Most on the Left would regard staying in the EU as a necessity towards any such ambition but that doesn’t mean the arguments in the new book The Left Case against the EU from Costas Lapavitsas should be discounted either. Leave? Remain? The key surely is Change.

Whether or not Labour can come out the other side of the seasonal break from Brexit starting to look more and more like the next Government will be the crucial question of early 2019. Jeremy Corbyn and the Strange Rebirth of Labour England by Francis Beckett and Mark Seddon revisits the roots of Corbyn’s rise to provide readers with credible optimism towards that end. Matt Bolton first wrote up his critique of Corbynism as a blog, describing it as possessing a ‘terrifying hubris’. Harsh but his was a critical accont that was decidedly well thought-out and deserving of a considered read. Now Matt, with co-thinker Frederick Harry Pitts, has turned their shared line line of argument into a book Corbynism : A Critical Approach. I wasn’t convinced by their answers but there are some very good questions raised, too good to simply be dismissed out of hand.

Here’s one question that most certainly needs asking will it be the economy, that shifts things in 2019, stupid? Yes, almost certainly. The collection Economics for the Many edited by John McDonnell is a platform for a comprehensive range of the kind of policies that will not only roll back austerity but in the process lay the foundations for a durable alternative. However any such project should also be about the quality of the lives we lead which is why Melissa Benn’s Life Lessons is such a vital companion volume. Making the case for a ‘national education service’ this book is an explicit critique of the managerialism that has monetised our children’s education. Of course the New Year is also a time to look back over the past twelve months. No one is better equipped to inject some biting satire into remembering the events of 2018 than cartoonist Steve Bell. If Steve’s latest collection Corbyn : The Resurrection, covering the years 2015-18 failed to make it as a stocking-filler my advice is to rush out and buy yourself a copy to be sure of a happier New Year.

Here’s one question that most certainly needs asking will it be the economy, that shifts things in 2019, stupid? Yes, almost certainly. The collection Economics for the Many edited by John McDonnell is a platform for a comprehensive range of the kind of policies that will not only roll back austerity but in the process lay the foundations for a durable alternative. However any such project should also be about the quality of the lives we lead which is why Melissa Benn’s Life Lessons is such a vital companion volume. Making the case for a ‘national education service’ this book is an explicit critique of the managerialism that has monetised our children’s education. Of course the New Year is also a time to look back over the past twelve months. No one is better equipped to inject some biting satire into remembering the events of 2018 than cartoonist Steve Bell. If Steve’s latest collection Corbyn : The Resurrection, covering the years 2015-18 failed to make it as a stocking-filler my advice is to rush out and buy yourself a copy to be sure of a happier New Year.

Of course neither Brexit nor Corbynism exist in a vacuum. Trump and the revival of the Democrats in the mid-terms, especially the breakthrough of new, young, Left candidates, was a 2018 Transatlantic expression of this. Where we go from Here is an account by Bernie Sanders of the two years since Trump’s election and what this means for the future of American politics. By the end of 2019 the next round of Democrats’ Presidential primaries will be fast approaching, making sense of the parallels and differences with our situation in the UK that Bernie helps reveal thus becomes increasingly vital.

Both Trumpism and Brexit have unleashed some ugly forces. The Chris-Howard Woods, Colin Laidley and Maryam Omidi edited collection#Charlottesville details one particular moment when a nakedly white surpremacist politics came up against militant resistance.

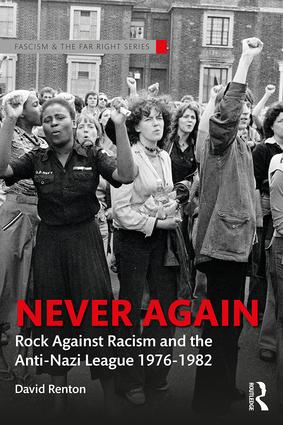

But for an insight into how to build a mass, popular and victorious movement around anti-fascism and racism there is no better book than David Renton’s latest, Never Again, a historiography of Rock against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League, 1976-1982. Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin in their co-authored National Populism describe the resurgent Right from Trump via the German Afd, Liga in Italy, and Marie le Pen in France to the Brexiteer ultras with ‘Tommy Robinson’ in tow as a revolt against Liberal Democracy. A useful schematic for understanding the causes, it however fails to address what a progressive, in particular anti-racist, alternative might look like. A much better, and hugely original, starting point therefore is the one outlined by Will Davies in Nervous States. Utilising a wide range of both analyses and examples Will points to how reason has declined and feeling has come increasingly to take its place. He doesn’t patronise the latter but via an understanding of it reasserts the cause of a rational, radical politics properly equipped for the era in which we live. Brilliant. What kind of political organisation may be up to the task of not only resisting the rise of this populist-racist right but also reclaiming the cause of reason versus reaction? Paolo Gerbaudo’s The Digital Party is a wide-ranging, and international, survey of those parties that have gone furthest to embrace the organisational changes the new modes of communication demand of us all and as such is a compelling read for the future of politics.

But for an insight into how to build a mass, popular and victorious movement around anti-fascism and racism there is no better book than David Renton’s latest, Never Again, a historiography of Rock against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League, 1976-1982. Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin in their co-authored National Populism describe the resurgent Right from Trump via the German Afd, Liga in Italy, and Marie le Pen in France to the Brexiteer ultras with ‘Tommy Robinson’ in tow as a revolt against Liberal Democracy. A useful schematic for understanding the causes, it however fails to address what a progressive, in particular anti-racist, alternative might look like. A much better, and hugely original, starting point therefore is the one outlined by Will Davies in Nervous States. Utilising a wide range of both analyses and examples Will points to how reason has declined and feeling has come increasingly to take its place. He doesn’t patronise the latter but via an understanding of it reasserts the cause of a rational, radical politics properly equipped for the era in which we live. Brilliant. What kind of political organisation may be up to the task of not only resisting the rise of this populist-racist right but also reclaiming the cause of reason versus reaction? Paolo Gerbaudo’s The Digital Party is a wide-ranging, and international, survey of those parties that have gone furthest to embrace the organisational changes the new modes of communication demand of us all and as such is a compelling read for the future of politics.

While some things change, others remain the same. The brutal, dehumanising treatment of the Palestinians by Israel continued in 2018. And this time the shooting by the Israeli army of unarmed protestors who joined Gaza’s Great March of Return offended even many of Israel’s hitherto staunchest supporters. But sadly still nothing seems to change. What a relief therefore to read Nathan Thrall’s The Only Language they Understand an unashamed search for a principled compromise, that won’t satisfy entirely either side but will most.

One of the welcome after-effects of Corbynism has to be the revival of a Left intellectual culture. One of the best examples of this is the journal Renewal.The latest edition in particular carries a superb piece by leftwing economist Christine Berry available as a free download ‘ how does a movement prepare for power.’ Compass has always confounded convention by combining the work of a think-tank with the ambition of being a campaign hub. Occasionally wrongfooted by the rise of Corbynism, the latest Compass publication The Causes and Cures of Brexit showcases their thoughtful strengths, not demonising the support for ‘Leave’ but seeking to understand its rationale, something too few even recognise. Also available as a free download, here. But my favourite popular-intellectual initiative of 2018 was the return of the political pamphleteer in the shape of Dan Hind’s excellent ‘New Thinking for the British Economy‘ series .

One of the welcome after-effects of Corbynism has to be the revival of a Left intellectual culture. One of the best examples of this is the journal Renewal.The latest edition in particular carries a superb piece by leftwing economist Christine Berry available as a free download ‘ how does a movement prepare for power.’ Compass has always confounded convention by combining the work of a think-tank with the ambition of being a campaign hub. Occasionally wrongfooted by the rise of Corbynism, the latest Compass publication The Causes and Cures of Brexit showcases their thoughtful strengths, not demonising the support for ‘Leave’ but seeking to understand its rationale, something too few even recognise. Also available as a free download, here. But my favourite popular-intellectual initiative of 2018 was the return of the political pamphleteer in the shape of Dan Hind’s excellent ‘New Thinking for the British Economy‘ series .

In the twentieth century it was 1917 that framed the efforts of those who followed in the footsteps of revolution. John Maclean by Henry Bell details Scotland’s flirtation with revolutionary politics while a special edition of New Formations marks the 2019 centenary of Rosa Luxemburg’s murder with a range of essays detailing her continuing influence and significance. The journal Twentieth Century Communism remains the unrivalled source of insights into 1917’s aftermath worldwide, the latest issue providing a rare focus on African communism. That aftermath is of course not unchanging, the first transformation we might date to the post 1956 New Left, chronicled in a brand new Socialist Register Reader with contributors ranging from Ralph Miliband and Jean-Paul Sartre to Rosana Rossanda and André Gorz.. And then a decade later a further convulsion, 1968, that in 2018 celebrated its 50thanniversary. The Voices of 1968 is an invaluable collection of original material from this most epic of years ranging right across Europe and the USA for its sources. Fiercely critical of the ‘official’ communist movement yet ardent defenders of its own particular interpretation of 1917, and Leninism more widely, John Kelly’s critical, yet not unfriendly, account Contemporary Trotskyism details the particular appeal of this version of a revolutionary politics.

Of course ‘revolution’ in the era of late capitalism has come to mean all manner of things. Alan Bradshaw and Linda Scott’s Advertising Revolution accounts rather brilliantly for the word’s evolution via a Beatles’ hit into a Nike advert and a message even Trump embraces. Taking a different tack Oli Mould in Against Creativity demolishes all manner of claims to ‘liberate’ body, soul and mind via a corporatised version of the power of the creative. Neither critique eliminates the necessity for social change, anything but, both however force us to tackle a bastardised vocabulary as a barrier to making it happen.

Of course ‘revolution’ in the era of late capitalism has come to mean all manner of things. Alan Bradshaw and Linda Scott’s Advertising Revolution accounts rather brilliantly for the word’s evolution via a Beatles’ hit into a Nike advert and a message even Trump embraces. Taking a different tack Oli Mould in Against Creativity demolishes all manner of claims to ‘liberate’ body, soul and mind via a corporatised version of the power of the creative. Neither critique eliminates the necessity for social change, anything but, both however force us to tackle a bastardised vocabulary as a barrier to making it happen.

Versemongering in the cause of social change has a long and rebellious history. Dread, Poetry & Freedom by David Austin provides not simply a biographical account of Linton Kwesi Johnson but a political history of the context of his poetry.

Fusing their poetry with street-level activism the ‘Poetry on the Picketline’ collective stand unashamedly in the tradition of LKJ’s campaigning performances. Their debut collection Poetry on the Picketline showcases what they bring to any protest party. At the core of much of this is an admirably do-it-yourself ‘We are all poets’ philosophy.To help us on our way, iambic pentameters and the like, there’s no finer how-to read than Michael Rosen’s classic What is Poetry?

Fusing their poetry with street-level activism the ‘Poetry on the Picketline’ collective stand unashamedly in the tradition of LKJ’s campaigning performances. Their debut collection Poetry on the Picketline showcases what they bring to any protest party. At the core of much of this is an admirably do-it-yourself ‘We are all poets’ philosophy.To help us on our way, iambic pentameters and the like, there’s no finer how-to read than Michael Rosen’s classic What is Poetry?

Undoubtedly the political novel of 2018 was Jonathan Coe’s Middle England. A funny, if sorry, tale of generational political drifts and divides set in the present and immediate past. An epic, read it before Brexit Day, 29thMarch, ouch!