More of a Marathon than a Sprint

08.08.16

Mark Perryman of Philosophy Football offers his reading selection for a Summer of Sport

Exhaustive? Exhausting more like. The never-ending summer of sport from Euro 2016, the British Grand Prix, English rugby down under, Test Match cricket, Le Tour, Wimbledon fortnight , Rio 2016 and then before you know it the football season has started. It was ever thus, the sport has just got bigger that’s all, if not always better.

To help navigate our way thought the cause and effect of the highs and the lows there’s no better place to start than John Leonard’s Fair Game an easy-to-read history of the clash between politics and sport. To take a more philosophical approach means engaging with competition vs participation, another one of those big match this versus that binary opposition which serve more to obscure than inform. Losing It by the superlative Simon Barnes teaches us more than we will ever need to know about the joys of not being on the winning side. But the sharpest divide in sporting culture has nothing to do with winners and losers but gender. Name a single sporting culture which isn’t fundamentally shaped by gender relations. Anna Kessel’s Eat Sweat Play is a popular read on a subject of complexity which reveals the structures that shape this sporting determinism. An absolutely essential read for the future of sport, any sport.

To help navigate our way thought the cause and effect of the highs and the lows there’s no better place to start than John Leonard’s Fair Game an easy-to-read history of the clash between politics and sport. To take a more philosophical approach means engaging with competition vs participation, another one of those big match this versus that binary opposition which serve more to obscure than inform. Losing It by the superlative Simon Barnes teaches us more than we will ever need to know about the joys of not being on the winning side. But the sharpest divide in sporting culture has nothing to do with winners and losers but gender. Name a single sporting culture which isn’t fundamentally shaped by gender relations. Anna Kessel’s Eat Sweat Play is a popular read on a subject of complexity which reveals the structures that shape this sporting determinism. An absolutely essential read for the future of sport, any sport.

Once every four years the Summer Olympics are so huge that for two and a bit weeks they both block out almost all other sport, and plenty more besides while providing a platform for sports that otherwise hardly ever get a look in. The latter is arguably one of the few remaining redeeming features of the Olympic ideal.

Dave Zirin’s fully updated Brazil’s Dance with the Devil deals with all these other less redeeming, anything but ideal, features of both the Olympics and football’s World Cup and their impact on Brazil in 2014 and 2016. Of course most of these failings are not new, from Jules Boykoff Power Games is a political history of the Games which explains the scale of the failure both historically and theoretically via the highly original concept of ‘celebration capitalism’. During Rio this will be our fayourite read between the breathlessly exciting sporting action on the TV.

Dave Zirin’s fully updated Brazil’s Dance with the Devil deals with all these other less redeeming, anything but ideal, features of both the Olympics and football’s World Cup and their impact on Brazil in 2014 and 2016. Of course most of these failings are not new, from Jules Boykoff Power Games is a political history of the Games which explains the scale of the failure both historically and theoretically via the highly original concept of ‘celebration capitalism’. During Rio this will be our fayourite read between the breathlessly exciting sporting action on the TV.

Ordinarily the combination of a European Championships and the fiftieth anniversary of ’66 would have turned 2016 into a footballing summer. For the English at any after Iceland 2 Poundland 1, no chance. Peter Chapman’s exercise in nostalgia Out Of Time reminds us of a year when for England, almost anything seemed possible, on and off the pitch, 1966. A perhaps less obvious year to choose to revisit with such English optimistic intent is 1996. But this was the year of England’s Euro 96, Britpop (actually English pop) and new Labour on the eve of a General Election landslide, including a majority of English seats. When Football Came Home by Michael Gibbons and When We Were Lions from Paul Rees both cover this epic tournament with one eye on the politics and culture of the time too. For thirtysomethings and older a really great read about something England have failed to do this century, make it to a tournament semi-final! Taking a longer historical view is Colin Shindler’s Four Lions which imaginatively chronicles English footballing history via the life, career and times of four England captains; Billy Wright, Bobby Moore, Gary Lineker and David Beckham. Taking a more conventional approach to all things post ’66 Henry Winter in Fifty Years of Hurt records with the finest of insights all that has gone wrong, and the reasons why, since that singular golden moment five decades ago. The paperback edition will make even more painful reading mind no doubt with he defeat to Iceland tacked on and the dawning of the age of Big Sam as England supremo. For a variety of studies of the modern game the edited collection by Ellis Cashmore and Kevin Dixon Studying Football provides a richness of academic explanations which are both rich in detail and deep in understanding.  But my top choice to pack for the new season’s away trip reading has to be And The Sun Shines Now by Adrian Tempany. I first read this superb book a year ago, cover-to-cover a review copy in just a few sittings but then it was promptly withdrawn because of the Hillsborough Inquest. This is a book you see that begins and ends with Hillsborough and in between deals with the mess modern English football has become. Delayed because of the Inquest and the legal restrictions of the legal proceedings on such a book, twelve months later it is if anything an even more powerful and compelling read.

But my top choice to pack for the new season’s away trip reading has to be And The Sun Shines Now by Adrian Tempany. I first read this superb book a year ago, cover-to-cover a review copy in just a few sittings but then it was promptly withdrawn because of the Hillsborough Inquest. This is a book you see that begins and ends with Hillsborough and in between deals with the mess modern English football has become. Delayed because of the Inquest and the legal restrictions of the legal proceedings on such a book, twelve months later it is if anything an even more powerful and compelling read.

Without the Ashes cricket struggles to get much of a look-in even during the summer months, selling off the live TV coverage to Sky has reduced wider public interest still further. Emma John’s Following On is therefore a timely reminder of cricket’s appeal, even when it’s not very good.

Football of course has been dominant for so long now in English sporting culture it is hard to imagine other models for how to consume sport, a five-day Test Match perhaps the most incongruous alternative imaginable. For me though my favourite other way to consume sport is cycling. Decentralised, free to watch, pan-European, on terrestrial TV, thousands ride the course to reach their best roadside vantage point, and the Brits always win, well almost. I’m talking of course about Le Tour. The classic account of this most famous of cycling contests, Geoffrey Nicholson’s The Great Bike Race, has recently been republished and is as good as it ever was, a superb mix of cultural history and sporting commentary.  And a novel to expand our understanding of what it takes to ride this greatest of all races? From Dutch author Bert Wagendorp now translated into English Ventoux the story of a group of friends who decide to ride to the summit of this most iconic of climbs and the effect the effort has on all of their lives. The Science of the Tour de France by James Witts takes a more practical approach. In spellbindng detail along with magnificent photography and graphics the author carefully explains what it takes to ride this most punishing of races spread over almost an entire month of varied and arduous competition. There is probably no rider better equipped to put that experience into words than David Millar, and he does precisely that in his very fine new book The Racer.

And a novel to expand our understanding of what it takes to ride this greatest of all races? From Dutch author Bert Wagendorp now translated into English Ventoux the story of a group of friends who decide to ride to the summit of this most iconic of climbs and the effect the effort has on all of their lives. The Science of the Tour de France by James Witts takes a more practical approach. In spellbindng detail along with magnificent photography and graphics the author carefully explains what it takes to ride this most punishing of races spread over almost an entire month of varied and arduous competition. There is probably no rider better equipped to put that experience into words than David Millar, and he does precisely that in his very fine new book The Racer.

What is special about cycling is the connection between competition and participation, what other sport can you use as a means to get to work, do the shopping, a family day out? Team Sky rider and Team GB Olympian sketches out precisely those connections in his amusing yet informative book The World of Cycling According to G .

The most basic sporting test however of human endurance remains running. Arguably the one truly universal global sport, requiring no equipment, no facilities, any body shape, and for the lucky few a route out of poverty too. Richard Askwith has established himself as one of the best writers on the sport, Today We Die A Little is Richard’s biography of one of the greatest long-distance runners of all time, Emil which reveals both what it takes physically to take one’s body beyond the limits of human endurance but also the political context of 1950s Eastern Europe which drove Zátopek to run. A truly illuminating read. But there’s one feat Zátopek failed to achieve, nor any runner after him either. Breaking two hours for the marathon. Ed Casear’s Two Hours combines investigative journalism, sports science and athletic travelogue to find out whether this near-mythical barrier might ever be broken.

Richard Askwith has established himself as one of the best writers on the sport, Today We Die A Little is Richard’s biography of one of the greatest long-distance runners of all time, Emil which reveals both what it takes physically to take one’s body beyond the limits of human endurance but also the political context of 1950s Eastern Europe which drove Zátopek to run. A truly illuminating read. But there’s one feat Zátopek failed to achieve, nor any runner after him either. Breaking two hours for the marathon. Ed Casear’s Two Hours combines investigative journalism, sports science and athletic travelogue to find out whether this near-mythical barrier might ever be broken.

And my sports book of the quarter? There is only really one choice. Not content with writing a peerless global history of football, The Ball is Round and a riveting account of all that is wrong with English football The Game of Our Lives David Glodblatt has now written both the definitive and best history of the Olympics, The Games. What David does so effortlessly well as a sportswriter is combine hard won facts and tales with original opinion and ideas to construct both a story and an alternative. The must have book for those late nights and early mornings on Olympics TV watch from Rio, and long after too.

And my sports book of the quarter? There is only really one choice. Not content with writing a peerless global history of football, The Ball is Round and a riveting account of all that is wrong with English football The Game of Our Lives David Glodblatt has now written both the definitive and best history of the Olympics, The Games. What David does so effortlessly well as a sportswriter is combine hard won facts and tales with original opinion and ideas to construct both a story and an alternative. The must have book for those late nights and early mornings on Olympics TV watch from Rio, and long after too.

Note: No links in this review toAmazon, if you can avoid purchasing from tax dodgers please do so.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’ aka Philosophy Football.

A Games That Belonged To The People

05.08.2016

Mark Perryman of Philosophy Football uncovers the hidden history of Barcelona ‘36

When the Rio Olympics begin tonight beyond the glitz and the glamour of the opening ceremony spectacle there will be popular protests right across the city. It was the same at London 2012 and the Vancouver Winter Games of 2010. Throughout the build up to both Sochi 2014 and Beijing 2008 there were global protest to force attention on LGBT discrimination and human rights issues in host countries Russia and China. But of course once the gold medal rush began the protests and concerns were almost universally marginalised. I suspect it will be more or less the same with Rio.

How do we manage both to enjoy and celebrate sport while maintaining some basic principles of equality and solidarity? Perhaps what we need is a political culture that takes sport seriously – what we do with Philosophy Football mixing sport and culture is one brave and audacious attempt to do precisely that – rather than treating it simply as a suitable add on for photo opportunities and celebrity endorsements of this issue or that.

For an idea of what might be possible a useful starting point would be to revisit the 1930s. This was of course the era of the rise of Mussolini and Hitler. Mussolini put great emphasis on football as the means of portraying his idealised fascist nation, Italy hosted and won the 1934 World Cup and retained the trophy four years later too at France ’38 on the eve of war. But it is Hitler’s Berlin Olympics of 1936 which are most widely remembered for the clash of political ideology and sporting spectacle. The four gold medals won by black American sprinter and long jumper Jesse Owens of course have come to symbolise the way sport can subvert an intended political message to devastating effect. But what scarcely gets mentioned is the widespread efforts of both the International Olympic Committee to make a positive case for the Nazi regime to host the Games in order to head off calls to boycott Berlin.Much of this lobbying was done by notorious anti-semite Avery Brundage who went on to become the President of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. This is the history the Olympic movement would prefer remained hidden.

But the 1930s was also the era of the Popular Front. A political culture that extended way beyond traditional definitions of activism. Inspired by both the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rising threat of fascism the Popular Front embraced literature – the Left Book Club – poetry, art, perhaps most famously Picasso and Miro, music – including Benjamin Britten, the festive and the celebratory as well as the militancy of street protests, notably in 1936,Cable Street. And sport played its part too.

But the 1930s was also the era of the Popular Front. A political culture that extended way beyond traditional definitions of activism. Inspired by both the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rising threat of fascism the Popular Front embraced literature – the Left Book Club – poetry, art, perhaps most famously Picasso and Miro, music – including Benjamin Britten, the festive and the celebratory as well as the militancy of street protests, notably in 1936,Cable Street. And sport played its part too.

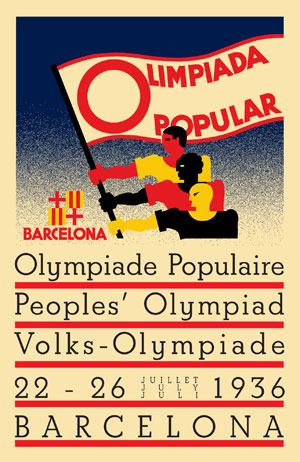

The Spanish Republican government took a political decision to boycott the Berlin Games. They correctly judged that with the Olympic movement barely interested in putting up any opposition Berlin would become a platform for Hitler and Goebbels to sanitise and propagandise for Nazism. Jesse Owens notwithstanding, they were proved absolutely correct. However this was no ordinary boycott. The Spanish government pledged to host a People’s Olympiad in the Republican stronghold of Barcelona with over 6,000 athletes from across the world taking part. Timed to take open just a few weeks before Berlin this would have been a powerful example in practice of a sporting internationalism vs the racialisation of sporting endeavour the Nazis were seeking to promote. Then, on the eve of the opening ceremony, Franco launched his murderous assault on the Spanish Republic, the country was plunged into civil war and the Games cancelled. Most athletes were forced to leave though some chose to stay and join the International Brigades in their fight for Spain’s land and freedom.

The point about Barcelona ’36 is that it didn’t happen in isolation. Other ‘alternative’ Games included Czechoslovakia’s 1924 National Gymnastics Festival organised by the Workers Gymnastics and Sports Association, the first Workers’ Olympics in Frankfurt 1925, Moscow’s Spartakiad of 1928, the Vienna Workers’ Olympics of 1931, a second Spartakiad of 1933 organised by the Red Sport International, the third and final Workers’ Olympics, Antwerp 1937. And there were alternative Women’s Olympics too, four in all 1922 Paris, 1926 Gothenburg, 1930 Prague and 1934 London.

It’s almost impossible to imagine anything of this scale of imagination and purpose today. Jules Boykoff in his brilliant new political history of the Olympics, Power Games, has a novel explanation of why such an alternative model of sport is so important rather being being simply, if necessarily, against this and that. He describes the Olympics, and other global sporting spectacles such as football’s World Cup, as ‘celebration capitalism’ juxtaposing this to Naomi Klein’s theorisation of ‘disaster capitalism’. For the duration of Rio we will be treated over and over again to the Olympian maxims of inspiration, regeneration and participation. Huge public and material investment in infrastructure and Gold Medal-winning performances to celebrate what, and benefit whom? To state this is to engage with a popular common sense,, not to moan and whinge about what Rio 2016 or London 2012 fail to achieve but to be inspired by Barcelona ’36 to shape a better sporting culture for all.

Philosophy Football’s Barcelona ’36 T-shirt is available from here

Don't Burn the Books

08.07.2016

A scorching hot list of summer political reading selected by Mark Perryman

A year ago as Labour sought to recover from the May General Election defeat halls were starting to fill up for Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership campaign rallies. But even as the halls got bigger and the queues round the block longer few would ever imagined that this would result in the Left for once being on the winning side. The overwhelming majority of Labour MPs never accepted the vote, they bided their time and chose the moment for their coup and in a fashion to cause maximum damage.

Richard Seymour’s Corbyn : The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics is to date both the best, and the definitive, account of what Corbyn’s victory the first time round meant. One year on the essential summer 2016 read.

Richard Seymour’s Corbyn : The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics is to date both the best, and the definitive, account of what Corbyn’s victory the first time round meant. One year on the essential summer 2016 read.

But as Jeremy Corbyn would be the first to admit his victory will never amount to much unless he can refashion what Labour also means. A Better Politics by Danny Dorling is a neat combination of catchy ideas and practical policies towards a more equal society that benefits all. Of course the principle barrier to equality remains class. In her new book Respectable Lynsey Hanley provides an explanation of modern class relations that effortlessly mixes the personal and the political. If this sounds easier written than done then George Monbiot’s epic How Did We Get Into This Mess? serves to remind us of the scale of the economic and environmental crisis we are up against.Labour’s existential crisis is rooted in competing models of party democracy and how this should shape a party as a social movement for change. An exploration of what a left populist mass party might look like and the problems it will encounter is provided in Podemos: In the Name of the People a highly original set of conversations between theorist Chantal Mouffe and Íñigo Errejón political secretary of Podemos, introduced by Owen Jones, what a line-up!

One of the saving graces of Labour’s crisis should be pluralism. To reject those who indulge in the simplistic binary oppositions of Corbynista vs Blairite. To begin with all engaged in the Labour debate should read the free-to-download book Labour’s Identity Crisis : England and the Politics of Patriotism edited by Tristram Hunt. There is much here on an issue vital post #Brexit yet scarcely acknowledged as important by most on both ‘sides’ One criticism though, why no contributors from the Left side, Billy Bragg, Gary Younge, the young black Labour MP Kate Osamor for example? Taking a tour round Britain to portray the state of the nation(s) is fairly familiar territory for writers on Britishness but Island Story by JD Taylor still manages to stand out thanks to a the author’s sense purpose, tenacity of the imagination, and a bicycle. Underneath the surface of any tendency towards a settled national narrative lies a bastardised version of English nationalism combining the isolationist and the racist to produce a toxic mix. As a shortish polemic The Ministry of Nostalgia from Owen Hatherley is more of a demolition than a deconstruction of the rewriting of our history that lies behind this, and all the better for it.

Anglo-populism is mired in the issue of immigration as a mask for its racism.Angry White People by Hsiao-Hung Pai encounters the extremities of this, the Far Right whose politics of hate have a nasty habit of not being as far away as many of us would like.In the USA the brutal institutionalised racism of its police force has sparked a mass movement which is reported with much insight by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s in her From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, an essential read if a similar popular anti-racism is going to emerge on this side of the Atlantic sometime soon. Of course #BlackLivesMatter didn’t emerge in a political vacuum, it connected movements that date back to the 1950s and 1960s, connections which are expertly made by one of the key Black political figures of both then and now Angela Davis in her new book Freedom is a Constant Struggle an absolutely inspiring read. Do the deepening fractures around race spell a new era of uprisings? Quite possibly though their political trajectory and outcomes remain uncertain. Joshua Clover comes down firmly on the side of the optimistic reading in his new book Riot.Strike.Riot while most wouldn’t be so sure. A handy companion volume would be Strike Art by Yates McKee which helpfully explains the protest culture created via the Occupy movement. Where the doubt remains is whether the such moments, direct action or insurrection, can generate a positive impact beyond their own milieu or locality.

Shooting Hipsters is a much-needed up to date account of, and practical guide to, how acts of dissent can breakthrough into and beyond the mainstream media. And for the dark side? Mara Einstein’s Black Ops Advertising details the many ways in which corporate PR operations have sought to colonise social media.

Shooting Hipsters is a much-needed up to date account of, and practical guide to, how acts of dissent can breakthrough into and beyond the mainstream media. And for the dark side? Mara Einstein’s Black Ops Advertising details the many ways in which corporate PR operations have sought to colonise social media.

It is out of history that inspiration for how to carve out a better future from the present is most likely to come. A Full Life by Tom Keough and Paul Buhle uses a comic strip to illustrate the life, times and ideals of Irish rebel James Connolly. Alternatively enjoy the extraordinary range of writing from the Spanish Civil War compiled by Pete Ayrton in No Pasaran! These were moments in a period of global change. Owen Hatherley’s carefully crafted The Chaplin Machine provides an insight into the aesthetic of revolution that was abroad at the time in the immediate aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution on a scale never seen before, or since. It is a period that is recorded with considerable skill by the twice-yearly journal Twentieth Century Communism the latest edition providing the usual ingenuity of range including Trotsky’s bid to live in 1930s Britain. outline of the basis for a cosmopolitan anti-imperialism. Of course there are plenty who would seek to bury all of this. David Aaronovitch comes to the last rites with his brilliantly written if flawed Party Animals which takes aim with his personal biography at the end of one history. An entirely different perspective is provided by the hugely impressive Jodi Dean and her latest book Crowds and Party an impassioned account of modern protest movements as the enduring case for a mass party of social and political change. Sounds familiar, trite even? Not the way Jodi argues it, mixing an acute sense of history with a visionary future.But the here and now of a super soaraway summer perhaps demands more immediate resources of hope than the promise of a better tomorrow.

My starting point for a today to look forward usually revolves around finding a recipe for a decent supper. Plenty of these to be found in The Good Life Eatery Cookbook with a mix of good-for-you, or more importantly in this instance me, temptingly delicious-looking photography and a philosophy behind it all that reminds me of that good maxim ‘small is beautiful.’ Of course no summer should be complete without a visit to the beach, highly recommended reading for the sun-lounger searching for a dash of a thriller for a mental getaway is Chris Brookmyre’s latest Black Widow which as always with Brookmyre is dark, twisted and entertaining. And for the children? Pushkin Press do the hard work for parents, tracking down the best in European kids’ books, translating, repackaging and producing such gems as Tow-Truck Pluck from the Netherlands. The perfect holiday read for families needing to be cheered up post-Brexit.

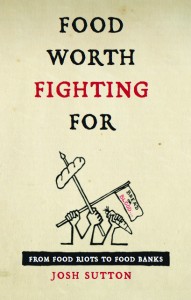

And my book of the quarter? Food is never far from most of our minds. Summertime picnics for the fortunate, worrying about what we eat and impact it has on our health for some, the spread of Food Banks testament to the failure of austerity politics. Few writers could appeal to both the modern obsession with food as well as to consciences concerned with those who don’t have enough of it to get by never mind baking off. But Josh Sutton does with his pioneering account Food Worth Fighting For. This is social history that packs a punch while written in a style and with a focus to transform readers into fighting foodies. Brilliant, and incredibly original.

And my book of the quarter? Food is never far from most of our minds. Summertime picnics for the fortunate, worrying about what we eat and impact it has on our health for some, the spread of Food Banks testament to the failure of austerity politics. Few writers could appeal to both the modern obsession with food as well as to consciences concerned with those who don’t have enough of it to get by never mind baking off. But Josh Sutton does with his pioneering account Food Worth Fighting For. This is social history that packs a punch while written in a style and with a focus to transform readers into fighting foodies. Brilliant, and incredibly original.

Note : No links in this review to Amazon, if you can avoid purchasing from off shore tax dodgers please do.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of the self-styled ‘sporting outfitters of intellectual distinction’, aka Philosophy Football.

#More in Common

22.06.2016

Mark Perryman explains why in any match of Hope vs Hate Philosophy Football knows which side we are on

The shocking news of MP Jo Cox's murder has affected us all. A terrible crime that begins with hate for a neighbour because of where they came from. A hate that is amplified by politicians and media to serve their own interests and never mind the consequences. A process that ends with this and who knows even worse to come.

Britain isn’t alone in suffering any of this, a tidal wave of hate-politics is sweeping Europe. The Freedom Party in Austria, Front National in France, AfD in Germany, Jobik in Hungary, Golden Dawn in Greece, Liga Nord in Italy and more. A racism that exploits and encourages division. A populism that offers easy answers to close down the space for difficult questions. A culture that promotes exclusion, intimidation and isolation.

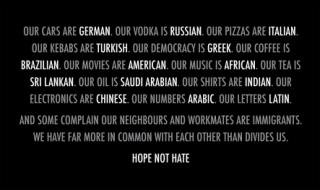

‘Our cars are German, our vodka is Russian, our pizzas Italian…’ Who would ever have imagined that coffee would replace tea as Great Britain’s favourite. Or wine overtake beer as the most popular tipple. Fish and chips vs Chicken Tikka Masala. Cheese and cucumber sarnies vs pitta and humous. Does this mean national identities no longer exist? Of course not. But we co-exist and for the most part are the better off for it.

‘Our cars are German, our vodka is Russian, our pizzas Italian…’ Who would ever have imagined that coffee would replace tea as Great Britain’s favourite. Or wine overtake beer as the most popular tipple. Fish and chips vs Chicken Tikka Masala. Cheese and cucumber sarnies vs pitta and humous. Does this mean national identities no longer exist? Of course not. But we co-exist and for the most part are the better off for it.

Immigration doesn’t happen by accident. We live in a world of bloody wars, extremities of inequality and increasingly the catastrophic social impact of climate change. These more than anything else cause rising levels of movement of population from every part of the world. And on our own continent European youth culture is interconnected in a way unimaginable only a decade or so ago. This is the easyjet generation of twitter, facebook and instagram. Thus living and working in another country is both possible and practical. Immigration? This is about emigration too. A Europe where another country which was once perhaps a holiday destination today provides a workplace.

Interconnections in a Europe of possibilities isn’t what most politicians talk about. In their absence hate fills the gap. That’s why Philosophy Football has always actively backed the Hope not Hatecampaign. While others have done far more than us we made our own contribution. We coined the slogan 'Hope not Hate', designed the logo, produced and donated banners to decorate the Barking cHQ in the succesful 2010 General Election campaign to defeat Nick Griffin and his BNP, helped raise funds and tramped the streets spreading the message. And so when we read that Jo Cox’s friends and family had chosen Hope not Hate as one of the campaigns to donate to in her memory, we wanted to find a means to contribute. Our 2016 Hope not Hate tee is towards that end, raising funds with a new design featuring a message for the better world she believed in.

Jo Cox was rare. She both understood why people move from country to country, some for work, others for safety, many for both. But she also had the courage to challenge these lies about immigration that exploit anxieties with reckless abandon. Inspired by her principles and ideals, our shirt features Jo's words from her House of Commons maiden speech 'We are far more united and have far more in common with each other than things that divides us'. A simple idea, we’d like to think while not uniquely British, a British value. Getting on with others, pulling together, sharing adversity for the greater good, bold and brave enough to engage with the other, celebrating our differences but not at the expense of one another. In the big match of hope vs hate knowing which side we’d rather be on thankyou very much.

The murder of Jo Cox didn’t come out of nowhere. A single lethal act but out of a mood that seeks to justify, legitimise, give respectability to a politics of hate. One singularly tragic consequence but against a background of countless other acts of hate. If politics is about anything it is about standing up for change, to challenge prejudice and misinformation, a vision of a better society for all. This is how we resist the drift towards the hateful.

Our simple act of remembrance has a practical aim. In place of our customary new shirt discount £5 will be donated for each shirt sold to Hope not Hate. If you can purchase at the solidarity price £10 will be donated. Remembrance and solidarity.

Hope not Hate 2016 shirt available from www.philosophyfootball.com

Campaign details from www.hopenothate.org.uk

Battle of Britons

15.06.2016

Mark Perryman previews England v Wales as competing versions of nationhood

The traditional ‘Battle of Britain’ match is of course England v Scotland, the very first recognised international football match dating back to 1872 and the most intense of rivalries ever since. The last time two ‘home’ nations met in a major tournament it was again England v Scotland at Euro 96. The spark in so many ways for the break-up-Britain agenda that was to follow the Blair government devolution referendums a year later and latterly transformed into the SNP ‘tartan landslide’. Once derided by Jim Sillars as ‘ninety-minute nationalists’ Scots today are so busy building a nation they can call their own they haven’t much time left over for their under-performing football team, ouch!

Instead it will be the Welsh who will take the field on Thursday against Scotland’s ‘auld enemy’. An encounter inevitably affected by the ugly scenes the weekend before in Marseille. It was the historian Eric Hobsbawm who once observed, “ The individual, even the one who only cheers, becomes a symbol of the nation himself.” This was sadly true of those brutalised encounters in the south of France. Though as my friend Julie Nerney who was there has pointed out the habit of most travelling England fans is to “learn where to go and not to when you travel to games. Avoiding the places where it was obvious there was a chance of things kicking off. Knowing what the signs of a flashpoint were and extricating yourself from any situation where you might simply end up in the wrong place at the wrong time.” And thus in Marseille as Julie reports “Bars in the main square of any town are a magnet for trouble. Many sensible fans give them a wide berth.” This is the hidden story behind the headlines about an episode like Marseille 2016. Meanwhile in another part of town I’d helped organise a fans’ mini tournament England v Russia, another mate, John Lunt, who played describes the experience, “Had fun, we may have lost all our games, but made a few friends when others were doing their best not to.”

Instead it will be the Welsh who will take the field on Thursday against Scotland’s ‘auld enemy’. An encounter inevitably affected by the ugly scenes the weekend before in Marseille. It was the historian Eric Hobsbawm who once observed, “ The individual, even the one who only cheers, becomes a symbol of the nation himself.” This was sadly true of those brutalised encounters in the south of France. Though as my friend Julie Nerney who was there has pointed out the habit of most travelling England fans is to “learn where to go and not to when you travel to games. Avoiding the places where it was obvious there was a chance of things kicking off. Knowing what the signs of a flashpoint were and extricating yourself from any situation where you might simply end up in the wrong place at the wrong time.” And thus in Marseille as Julie reports “Bars in the main square of any town are a magnet for trouble. Many sensible fans give them a wide berth.” This is the hidden story behind the headlines about an episode like Marseille 2016. Meanwhile in another part of town I’d helped organise a fans’ mini tournament England v Russia, another mate, John Lunt, who played describes the experience, “Had fun, we may have lost all our games, but made a few friends when others were doing their best not to.”

Little of this features in how most would think of the Englishness on parade at Euro 2016. Britain is a mix of contradictions, at home right now. Bathing in the collective and transnational experience of being European via the Euros while according to the referendum polls more than half the country couldn’t exit the continent fast enough For the English such contradictions are exacerbated by a very particular identity crisis. When England and Wales line-up for kick off each set of players, and fans will belt out their respective National Anthems. The Welsh, Land of our Fathers, while the English, like the Northern Irish, have to sing somebody else’s. Eh? That’s right us and the Northern Irish don’t have an anthem as every other country does, instead we have to sing an anthem that belongs to somewhere else, Great Britain. Yet the English tenaciously cling to an anthem which isn’t even ours as a source of great comfort. “Long to Reign Over Us, Happy and Glorious ” in those two lines the English contradictions of subjecthood neatly summed up.

American author Franklin Foer in his book How Soccer Explains the World points to the range of forces of globalisation which threaten this settled subjecthood founded on an unchanging notion of what it means to be English. Take a look at the players on any Premier League pitch, in the technical area the managers, coaches and backroom staff, the ownership of the bigger, and some smaller, clubs, the audience in the stands and via TV, the exchange of playing styles and tactics. There is very little left about our football which is precisely English.

Despite these forces of Europeanisation and globalisation however Foer makes a key point about soccer(sic) and culture; “ Of course, soccer isn’t the same as Bach or Buddhism. But it is often more deeply felt than religion, and just as much a part of the community’s fabric, a repository of traditions.” This is why England v Wales is always going to be about more than a football match.

An Englishness subject to imperial and martial tradition helps explain the ugly saliency of immigration as an issue in the Euro referendum non-debate and this reminds me of Satnam Virdee’s description of 1970s Powellism.

A powerful re-imagining of the English nation after empire, reminding his audience it was a nation for whites only. In that historical moment the confident racism that had accompanied the high imperial moment mutated into a defensive racism, a racism of the vanquished who no longer wanted to dominate but to physically expel the racialised other from the shared space they occupied, and thereby erase them and the Empire from its collective memory.

The make-up of the England team might appear a powerful antidote to these forces of reaction. But unlike the Welsh, and most particularly the Scots, the English barely possess a civic understanding of nationhood, instead it is mired in the racial. A football team may project some kind of alternative sense of being English but in the absence of political forces to make that argument it’s not enough. In June 2016 that couldn’t be more obvious.

None of this will help us predict the score when Bale’s Welshmen take on Rooney’s Englishmen but it certainly helps us understand how such an encounter is framed, consumed and understood. Performance isn’t something restricted just to the pitch y’know.

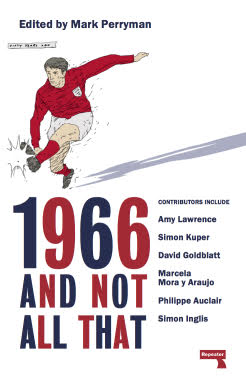

Mark Perryman is the editor of the new book 1966 and Not All That published by Repeater Books and available from Philosophy Football

Never Stopped us Dreaming

10.06.2016

As Euro 2016 begins Mark Perryman offers an 11-point plan finally to end England’s years of hurt.

Five decades on from England’s solitary tournament triumph and as the team prepare yet another effort to end these proverbial 50 years of hurt at Euro 2016 it seems as good a time as any to consider a diagnosis. Given it is the Football Association as the game’s governing body that is responsible for fulfilling the ambition a decent starting point is to ask what the FA is for? Football writer Barney Ronay provides a very reasonable answer:

Five decades on from England’s solitary tournament triumph and as the team prepare yet another effort to end these proverbial 50 years of hurt at Euro 2016 it seems as good a time as any to consider a diagnosis. Given it is the Football Association as the game’s governing body that is responsible for fulfilling the ambition a decent starting point is to ask what the FA is for? Football writer Barney Ronay provides a very reasonable answer:

“ The real problem for the FA is that it has no real power. It is essentially a front , a fluttering ceremonial brocade of a national sporting body. Football may be rich and powerful, but the FA exists at one remove from this, like Prince Charles complaining pointlessly about architecture from the sidelines.”

And he makes the point that the health of a football nation depends on the active co-operation of forces beyond the sport.

“ The FA neither owns nor controls the mechanics of roots football. It has no power to dictate what Premier League clubs do with young players. It isn’t the nation’s PE teacher. It is instead something of a patsy. One of the FA’s significant functions is to act as a kind of political merkin for the wider problem. Which is, simply, access for all: the right to play, a form of shared national wealth that has been downgraded by those in power for decades.”

Absolutely, the state of the country’s playing fields and publicly owned sports facilities portray a football nation that doesn’t know how to look after itself. It wasn’t the FA’s gross negligence that concreted over football pitches, privatised council leisure facilities to turn them into middle class domains, refused to control fast food and sugar-heavy drinks leaving them to spike up obesity levels and turned childhood into a daily fright-zone killing off three-and-in, jumpers for goalposts, pavement kickabouts within a generation of ’66. No, we can put all of that sorry mess to neoliberal governments from Thatcher onwards.

This is the political context of those years of a failing England team Deregulation, of state and sport. After selling off the elite level of their sport, the Premier League – football’s own version of deregulation - FA as a result has been left with one major responsibility that dwarfs any the others remaining, the national team. To turn that into a responsibility to be proud of and in turn help shift the balance of power and influence from football’s business to sporting interests the ambition has to be to re-establish the England team at the pinnacle of our sport. To do so means challenging sectional and commercial interests for the common good, to ensure the reality of an inclusive England that belongs to all, to celebrate being part of a world game which at its very best is founded on equitability.

To that end I offer an 11-point plan to end the 50 Years of Hurt.

1.Fifty @ 50

Fund 50 grassroots football coaches to provide free coaching support for primary age children, boys and girls. And as a support network approach every player who has represented England from ’66 onwards, every manager, assistant and backroom staff too, offer them a mentoring role for coaches, the kids and their families, with an agreement to provide 50 hours of such support a year. Establish a trust fund to ensure Fifty @50 has the finances to still be around in 2066.

2. The Bobby Moore Centre at Wembley

Right next to Wembley Stadium is one of those facilities providing a number of 5-a-side pitches. It’s privately owned, of no benefit to the FA. What a wasted opportunity. Purchase it outright as the FA’s Bobby Moore Centre, use it as a showpiece to introduce kids, their parents, their club coaches to all that England are trying to achieve at the under 11 level.

3.Take England back on the road

From 2000 to 2007 the old Twin Towers Wembley closed for demolition and reconstruction. Instead England internationals were played not just at Anfield, Old Trafford, Villa Park and St James’ Park but also Ipswich, Leicester, Derby, Southampton, Middlesbrough and Leeds. An England game became a local event and all the more special for that. The support more genuinely national than ever before. The enthusiasm for England up and down the country at World Cup 2002, Euro 2004 and World Cup 2006 surely in part a result. Reopening Wembley squandered all of this. Take England back on the road every year.

4. Schoolboys and schoolgirls double-header international

When the old Wembley closed the tradition of the annual schoolboy international ended with it. Bring them back but with a couple of twists. Alternate between Wembley and one of the top club grounds in the North, make it adouble-header, boys and girls.

5. Bring back the home nations but more too

Bringing back the home nations as an end-of-season tournament for the Under-21s, when not clashingg with their Euros with the added spice of a guest nation. Germany or Argentina for starters, Poland or Australia would attract large expat support, an African team provide experience of coping with unfamiliar playing styles. Run mens and womens tournaments side by side just like cricket and rugby do,

6. Football at the Commonwealth Games

Apart from England, and the other GB nations, every other country gets to play in two global football competitions, the World Cup and the Olympic Games, should they qualify of course. England don’t because Olympic representation is under the banner of ‘Team GB’. There is though another global tournament both England and the home nations could enter to get this crucial extra experience, the Commonwealth Games. Except football unlike rugby sevens isn’t a Commonwealth Games sport. Why on earth not?

7. A squad penalty shoot-out league

Once England have qualified establish a weekly training ground penalty shoot-out competition. Officiated by FA staff, for a dedicated website with a league table of results. And for the final round, the last home friendly before a tournament ends with a penalty shoot-out and fans asked to help by doing everything they can to put our players off.

8. No more Pride, Passion, Belief

‘Pride, Passion, Belief’ used to be the big screen message at Wembley immediately before kick-off for England internationals. Thankfully it’s been taken down but the sentiment remains. They’ll get a team to a Quarter-Final but by now we should have learned not enough to win trophies. The foreign influence if anything hasn’t gone far enough. Owning up to our technical ability deficiencies requires a cultural shift that has to come from below.

9. Bid to host age group World Cups and European Championships

Bid for World and European age group championships. Given half a chance we’ve proved across sports and Olympics to be rather good hosts, and for football we already have the facilities in place and all the evidence suggests decent crowds too.

10. A National Anthem we can call our own

God Save the Queen isn’t England’s anthem. If its good enough for Wales to have one of their own why not us? A song no longer about an institution, but about the nation we’d like to become. It would make the moment when the Anthem is sung a special moment rather than one draped in the otherness of officialdom. Jerusalem, yes please.

11. A 1966 Fiftieth Anniversary FA Congress

An FA Congress bringing together players, coaches, supporters and administrators representing every level of the English game. Football has changed dramatically since ’66, some for the better, some not. But the autocratic way in which it is run has stood absolutely still, if anything it has moved backwards. A Congress to debate in broad terms English football’s future as part of a process towards running the game for all, not just for some.

Does all this add up to England wining the World Cup at some unspecified, or as the current FA Chairman foolishly put it, specified date in the future? Quite possibly not, but the issue here is there is only so much an FA that has given up all its powers to govern the game can do. This plan could be activated by the FA even in their much reduced role. Crucially this would signal a start towards reclaiming the primacy of the national team.

New European and World Champions do emerge, France and Spain have gone from also-rans in ‘66 to finalists and winners. England does manage regularly to reach the quarter-finals, upgrading to becoming regulars in the last four shouldn’t be entirely beyond us. Croatia, Turkey, Bulgaria, Holland and Sweden have all matched that achievement so why with some modest improvements to our situation shouldn’t England? Because both after ’66 the FA utterly failed to act to build on that success, instead assuming there would be more of the same to come. There wasn’t. And then after coming so close again in ’90 the FA did act but with results that proved to be of no help to the England team at all. Many would argue these resulted instead in diminishing whatever prospects it might continue to have. As England line-up in Marseille with a youthful squad threatening to spark an enthusiasm that has scarcely existed since the woeful campaigns at World Cup 2010 and 2014 it is high time to look beyond getting out of a Group. Rather what we really need is a fundamental repositioning of the national team in relation to the game. A people’s England we can all be proud of and part of, and you never know march behind on a victory parade. C’mon, we have the right to dream don’t we?

Mark Perryman is the editor of the new book 1966 and Not All That. Published by Repeater Books and available from here

Mark Perryman is the editor of the new book 1966 and Not All That. Published by Repeater Books and available from here

Catching up with Portugal

01.06.2016

50 years ago England beat Portugal in the ’66 World Cup Final but Mark Perryman argues English decline has left England racing to keep up with their Euro rivals

Thursday night’s pre-Euro England friendly versus Portugal is bound to provoke a 50th anniversary revisiting of England’s best match of the ’66 World Cup. No, not the much feted Final, rather many would argue it was the semi against Portugal. Eventual Golden Boot winner, awarded to the tournament’s top goal-scorer, Eusébio, was in his superlative pomp with the 82nd minute penalty he scored pushing England all the way. Never mind though, the contribution of Bobby Charlton to England’s campaign has tended to be overshadowed by Geoff Hurst’s hat-trick in the Final but it was Bobby’s brace that saved England in the semi, the team running out eventual 2-1 winners.

Thursday night’s pre-Euro England friendly versus Portugal is bound to provoke a 50th anniversary revisiting of England’s best match of the ’66 World Cup. No, not the much feted Final, rather many would argue it was the semi against Portugal. Eventual Golden Boot winner, awarded to the tournament’s top goal-scorer, Eusébio, was in his superlative pomp with the 82nd minute penalty he scored pushing England all the way. Never mind though, the contribution of Bobby Charlton to England’s campaign has tended to be overshadowed by Geoff Hurst’s hat-trick in the Final but it was Bobby’s brace that saved England in the semi, the team running out eventual 2-1 winners.

Two years later, once more at Wembley, Charlton’s Manchester United, with Bobby scoring twice, again disappointed Eusébio . United were runaway winners thrashing Benfica, 4-1 to become the first English side to lift the European Cup.

The United side of course weren’t all English. Northern Irishman George Best, Scot Paddy Crerand, Irishmen Shay Brennan and Tony Dunne were vital parts of the team. On any other day Scot Denis Law would have been in the starting eleven too but he missed the game through injury.

In club football the Anglo-Celtic mix of ’68 United was replicated by other English clubs to deliver stunning European Cup successes. Between 1976 and 1984 seven out of eight European Cups were won by Liverpool (4 times), Nottingham Forest (twice) and Aston Villa. The sole exception? Hamburg, led by one Kevin Keegan. But this club success served to mask the enduring pattern of the national team’s decline while off the pitch hooliganism became almost indelibly connected with being an England fan abroad. Decline and moral panic proved a potent mix. In the New Society, then the house journal of a public sociology, Stuart Weir was one of the few commentators to identify not only the effects but the causes too:

Football is a popular sport, but it belongs to the world of Mrs Thatcher, Howell (Denis Howell, ex Labour Minister of Sport) and Sir Harold (Sir Harold Thompson, FA Chairman), not to the fans. Though workers formed and ran many of the leading clubs, they and the game’s major institutions - the FA and Football League - are now remote from the fans who keep the game going. The clubs are under the control of local business elites who restrict the participation of their followers to separate supporters’ clubs. The young fans get the worst deal. They are herded about with scarcely any respect. If they travel to away games, they are kept strictly segregated at all times and often end up in a pen at the home ground, with a poor view of the match.

Weir was reporting from Italia ’80 where the volume of tear gas fired into the English end at one game was so huge that play had to be temporarily stopped as the players were badly affected too.

Italia 90, a decade on, for one glorious moment seemed to put an end to the ignominy on the pitch and the lethal consequence of how fans were being mistreated, Hillsborough ’89. A World Cup semi-final, the first in 24 years after ’66, scraping past reigning European Champions Holland in the Group, thrilling victories over Belgium and Cameroon, and then the manner of the final exit, on penalties against West Germany. Gazza’a unforgettable tears combined with the culture clash of New Order’s World in Motion and Luciano Pavarotti’s Nessun Dorma.

A new dawn for the England team seemed to beckon. Instead English decline continued while other countries caught up and then overtook. Portugal? They beat us in the quarters at Euro 2004, and 2 years later at the same stage in World Cup 2006. Since World Cup ’66 England have failed to beat Portugal every time they’ve met in a competitive fixture. England’s last semi was twenty years ago at Euro 1996 , a home tournament. As for the rest, not counting the acknowledged European superpowers of World Football, Germany and Italy, the following countries have made it to a World Cup or Euro semi in that time. The Netherlands five times, Portugal four, France and Spain thrice each, Turkey twice, Croatia, Greece and the Czech Republic once apiece. England with not one semi-final in twenty years are perennial quarter-finalists at best, not semis or Finals, and even that position is now under threat with exits at the World Cup last 16 stage in 2010 and not getting out of their group in 2014. Euro 2012 we did at least make it to the quarters and against all expectations too. France this summer will be the big test to see if England can re-establish themselves in the tournament last eight, But compared to others’ records since the last time England made it to a semi this remains a piss-poor ambition.

But of course for the English winning is what most of England expects. Hence decline, in football as much as anything else is remarkably difficult to recognise let alone accept. We don’t expect to have to measure ourselves against the likes of Portugal do we? To be overtaken, left in their wake, borders on the unthinkable. Yet this is the dawning, if uncomfortable, reality. And in this manner in June two discourses, of the Euro Referendum and the Euro Championship are likely to become hopelessly entwined, inseparable in fact. Perhaps a semi and a vote to remain might combine to satisfy a new ambition. To be part of changing, but not to lead, Europe, towards the better for the both of us. But to get there, football-wise, we’ll need to win a quarter-final for the first time in twenty years. And our most likely opponents at that stage, according to my Euro wallchart ? Portugal. Neat.

Mark Perryman is the editor of 1966 and Not All That recently published byRepeater Books and available direct fromPhilosophy Football

An Imagined Community of Eleven Named People

15.05.16

Mark Perryman explores what Monday’s announcement of the England Euro 2016 squad tells us about modern Englishness

The backpages will be full of hopeful optimism after the announcement of England’s provisional squad for Euro 2016. A squad full to bursting point with youthful promise it is the England fan’s lot to believe for 50 years it can never be as bad as the last time but never as good as the first and only time either.

The backpages will be full of hopeful optimism after the announcement of England’s provisional squad for Euro 2016. A squad full to bursting point with youthful promise it is the England fan’s lot to believe for 50 years it can never be as bad as the last time but never as good as the first and only time either.

I was six at the time of England winning the World Cup in ’66. Despite it remaining somewhat of an obsession of mine – to declare an interest I’ve just edited the collection 1966 and Not All Thatto mark the 50th anniversary – I have no significant memories. Well apart from one, being Daddy’s little helper collecting tickets on the gate at the Tadworth, Walton and Kingswood summer flower show. It rained and nobody came, years later I realised why after checking the date, clashing with the England vs Argentina quarter-final was never going to attract any but the most dedicated of horticulturalists.

Four years later and I was a tad more conscious of the appeal of World Cup consumption for adolescent boys. This is how a particular version of masculinity formed. Ahead of Mexico ’70 garage forecourts had become a battleground for collectables, not that we called them that at the time. Fill up with enough petrol and all manner of goodies to complete collections. The Esso offer was ‘The 1970 World Cup Coin Collection’. I’ve still got mine, the greats from ’66, Banks, the Charlton brothers, Moore, Hurst and Peters alongside the thrusting new stars with Leeds United to the fore – Allan Clarke, Terry Cooper and Norman Hunter. Leeds were in their pomp, Division One Champions the previous season 1968-69, runners-up to Everton 1969-70. They lost the FA Cup Final too that year, the first I can properly remember, to Chelsea and an historic Cup Final too because it was the first to be settled by a replay. The World Cup? My memories are only slightly better, the Final watched live in colour on the TV, a first , round a friend, Grant Ashworth’s, house.

Fragments of childhood memories, a mix of history, family, changes in consumption, technological developments affecting how we enjoyed our leisure time, a sense of some kind of north-south divide played out on a football pitch. Flash Chelsea, most of whose first team seemed to live in the leafy suburbs just like me, versus a Leeds of grainy, hard-faced northern-ness. Then the whole lot of them coming together for the common cause, fighting the heat and the altitude of Mexico in England’s name. The squad made heroically wholesome and real via my much-treasured and, by the time of the tournament, complete coin collection. Monday’s England squad announcement for the Euros performs more or less the same function. Never mind the case for Kane and Vardy leading the line versus old campaigner but underperforming Rooney Or taking a risk on the injured pair Jordan Henderson and Jack Wilshire. There’s the odd surprise Man Utd starlet Marcus Rashford and the well-deserved return of Andros Townsend too. Fabian Delph? Well that’s one got me stumped I must admit, the clamour for Mark Noble was well-deserved making Delph’s inclusion all the more perplexing. No never mind all that. Rather the squad with name and number on the back all will perform historian Eric Hobsbawm’s much-quoted dictum “ an imagined community of millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people."

My 1970s meant secondary school and England’s failure. The dismal World Cup Qualifier ’73 game against Poland the beginnings of my proper football memories, or should that be nightmares? A youngish and incredibly cocksure Brian Clough in the studio with others of this verbally pugnacious sort, Malcolm Allison, Derek Dougan, Paddy Crerand, giving it their all. I seem to remember a year or so later a BBC Play for Today telling the story of watching the game from the point of view of a Pole living in England. The first mutterings, post-Powellism, of a multicultural conversation. Not on the pitch mind, another of my adolescent collectables is ‘The 1973 Esso Top Teams’, the four home nations’ squads united to form one Top 22. Not one of the players from the England, Scots, Welsh and Northern Irish line-ups pictured is black. It would be facile to suggest that the exclusion was anything to do with racism, there simply weren’t the top black players to pick in those days.

However it would be equally facile to pretend that the nostalgia so many of us share for an earlier, pre Premier League big business football isn’t framed also by the racialisation of Englishness. The vocabulary is important here. The Parekh Report The Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, published in 2000, attempted to carefully navigate the differences between racism and racialisation:

“Britishness, as much as Englishness, has systematic, largely unspoken, racial connotations. Whiteness nowhere features as an explicit condition of being British, but it is widely understood that Englishness, and therefore by extension Britishness, is racially coded… Race is deeply entwined with political culture and with the idea of nation, and underpinned by a distinctively British kind of reticence – to take race and racism seriously, or even to talk about them at all, is bad form, something not done in polite company. This disavowal… has proved a lethal combination. Unless these deep-rooted antagonisms to racial and cultural difference can be defeated in practice, as well as symbolically written out of the national story, the idea of a multicultural post-nation remains an empty promise.”

Ramsey chose an all-white 1966 World Cup-winning squad not because he was racist but because these were the best players at his disposal. And the same was true of most club sides well into the 1970s. Likewise when Roy Hodgson announces his squad selectionhe is hardly indulging in the proverbial ‘political correctness gone mad’ when a majority of his players are Afro-Caribbean and mixed race. The fans? In almost all cases couldn’t give a damn, a winning performance is all that matters.

The issues perhaps get a tad more complex, not to mention fraught, when as a result of globalisation and migration players increasingly are qualified to play for more than one national team. The loudest booing of a Black player I’ve ever witnessed at Wembley? When England played Ghana and Danny Welbeck, now injured so won’t be making it to Euro 2016, whose parentage meant he could have played for either team, came on as an England substitute. The moment he crossed that touchline in a senior international the chance of him ever representing Ghana was gone and the away fans let him know the depth of their disappointment.

Satnam Virdee describes the essence of a very particular version of English racism, Powellism as:

“ A powerful re-imagining of the English nation after empire, reminding his audience it was a nation for whites only. In that historical moment the confident racism that had accompanied the high imperial moment mutated into a defensive racism, a racism of the vanquished who no longer wanted to dominate but to physically expel the racialised other from the shared space they occupied, and thereby erase them and the Empire from its collective memory.”

It is to football’s credit that the England team has been such a powerfully symbolic barrier to these inclinations towards exclusion and expulsion. Of course racism persists, football can only achieve so much, contradictions and contestations remain in and out of the game, but to dismiss the achievement only nurtures the pessimism about the human condition that allows racist attitudes to flourish and grow.

To this extent England’s ‘years of hurt’ could legitimately be reconstructed instead as decades of healing. Not enough to shape a winning football team out of a rapidly changing society mind. Though with the greatest respect to Wales, given a relatively easy Euro’s draw and a squad of youthful promise, not to mention the goal-scoring sensation this season Jamie Vardy has become, well let’s just say an England fan’s hope springs eternal. And given the scale of these changes the multicultural team remains scarcely representative. There remains no players from an Asian background within sight of selection, Danny Welbeck would have been one of the few players of an African heritage selected , if Jack Grealish hadn’t had such a dismal season at Aston Villa and made it into the team he would have been the lone representative of one of England largest migrant communities, the Irish (though many others obviously choose to represent Ireland perhaps the question should be asked why) another significant migrant community, the Chinese remains unrepresented as do the Turkish and apart from Phil Jagielka who failed to squeeze in to the squad there are no obvuious contenders with Polish or other former East European nations’ family connections either. And unlike the ’66 squad, which included full back George Cohen, no players of the Jewish faith either.

None of this is to advocate that much misunderstood practice, positive discrimination. But it does reveal the narrowness of the particular version of multiculturalism the England team has come to symbolise. And at an elite level the narrowness of the communities from which football recruits, a weakness that Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski in their essay Why England Lose contrast with the much wider recruitment base of modern German football, not that they’re anything to worry about mind, what have the losing side in ’66 ever won? Answers on a big postcard please.

Mark Perryman is the co-founder of Philosophy Football and the editor of the new book 1966 and Not All That available from here

Football’s Greatest Hurt of All

28.04.16

Mark Perryman argues Hillsborough needs to be understood not just as a human tragedy but as a consequence of how football was changing whilst the golden moment of 1966 faded in the popular memory of the late 1980s.

One year after Hillsborough was Italia ’90. Fondly remembered today for Gazza’s tears, an evening, or three with Gary Lineker and the culture clash of Pavarotti’s Nessum Dorum vs New Order’s World in Motion.

One year after Hillsborough was Italia ’90. Fondly remembered today for Gazza’s tears, an evening, or three with Gary Lineker and the culture clash of Pavarotti’s Nessum Dorum vs New Order’s World in Motion.

But the actuality of the time was that up to the semi-final against you know who as a tournamen Italia '90 was dominated by what had become known as ‘The English Disease’. For the preceding five years all English club sides had been banned from European competition, an unprecedented punishment following crowd trouble involving Liverpool fans at the Heysel European Cup Final resulting in the death of 39 Juventus fans. This was an era when going to football required an unavoidable clash with trouble. Mass arrests, games dominated by what FA Chairman Sir Andrew Stephen described in 1972 as “the madness that takes place on the terraces”. Pitch invasions, games halted and abandoned. Riots accompanying European away trips, in 1974 Spurs Manager Bill Nicholson after one famously pleaded with his supporters “This is a football game –not a war.” Not for some it wasn’t. Mounted police deployed on the pitch to keep some semblance of order. In 1977 Man Utd were forced to play a ‘home’ European tie at Plymouth Argyle’s ground, the furthest away possible from Old Trafford but still in England, punishment for their rioting fans. The FA fined because of the riotous misbehaviour of England fans at tournaments. Players knocked unconscious by missiles thrown from the terraces. Games forced to be played behind closed doors. Fatalities. In 1985 the Bradford stadium fire, 56 deaths. On the same day a teenager dies at St Andrews when fighting breaks out between Leeds and Birmingham City fans.

Not nice, but hardly a surprise, The Sunday Times after the Bradford fire described football as “a slum sport played in slum stadiums increasingly watched by slum people, who deter decent folk from turning up.” It had taken less than two decades for English football’s 1966 golden moment to lose almost all its shine. Following the failures to qualify for the 1974 and 1978 World Cups England on the pitch finally made it to the 1980 European Championships hosted by Italy. The team were more or less back to the pre-1966 standard, finishing third in their Group and thus failing to make it to the semi-final played between the two Group winners and runners-up. It was off the pitch that the huge change in what England had become since ’66 was most evident. Other countries had a domestic hooligan problem, however this era England was virtually unique in exporting it to make trouble at Euros and World Cups. It was an unwelcome side show that would more or less persist through to Euro 2000 twenty years later until a seismic change in England fan culture occurred faraway amongst the 10,000 England fans who travelled out to Japan 2002 and England abroad has never been the same old, bad old, ever since.

One of the architects of the successful organisation of World Cup 1966, now Shadow Minster of Sport, Denis Howell found himself describing England fan trouble at Euro ’80 as a “National Disaster”. He wasn’t alone, when asked to comment on his team’s fans England Manager Ron Greenwood described them as “Bastards.” Suggesting “I hope they put them in a big boat and drop them in the ocean half-way back.” FA Chairman Harold Thompson added his own description of England supporters “ Sewer-rats.” This was the dominant discourse around what it mean to follow England for the fifty years’ of hurt middle two decades 1980-2000. For a long time few would challenge it as Stuart Weir bravely did writing for the then sociology house journal New Society reporting from the England away end at Italy ‘80.

“ The Italian police were slow to react, but made up for that by the extreme nature of their reaction. First, squads of police ran out of one of the tunnels and waded into any English fan within reach, regardless of whether they were involved in the affray or not. Shortly afterwards, riot police lined up on the other side of the moat and fired tear gas canisters into the great mass of English supporters in red, white and blue, who were nowhere near the original fracas.”

Weir accurately locates the skewering of the discourse in terms of the class relations already underpinning modern football twelve years before the abomination the Premier League would become.

“ Football is a popular sport, but it belongs to the world of Mrs Thatcher, Howell and Sir Harold, not to the fans. Though workers formed and ran many of the leading clubs, they and the game’s major institutions - the FA and Football League - are now remote from the fans who keep the game going. The clubs are under the control of local business elites who restrict the participation of their followers to separate supporters’ clubs. The young fans get the worst deal. They are herded about with scarcely any respect. If they travel to away games, they are kept strictly segregated at all times and often end up in a pen at the home ground, with a poor view of the match.”

James Erskine’s superb documentary film of Italia 90 One Night in Turin, heavily based on the peerless Pete Davies book of the same tournament All Played Out,memorably opens with a long sequence of violent crowd trouble.Except this wasn’t anything to do with football it was the Trafalgar Square Poll Tax riot of earlier that summer. I can still remember this Saturday afternoon. Shamefully as someone who prides himself on his leftwing principles I can’t claim to have been marching and demonstrating myself. Instead I was in a West End cinema and when the closing credits rolled a concerned box office manager appeared on stage to announce it was unsafe for anyone to leave. The West End was in flames with every plate glass window in the vicinity smashed to smithereens. Later that night on the tube home I listened in to conversations of groups of lads who’d also been held up, this time from leaving home games across the capital and regretting they’d missed out on all the violent fun.

The football violence of the 1980s cannot be entirely divorced from a period not just of increasing social division but mass mobilisation and more than occasional public disorder. Huge CND marches and associated direct action, 1981 inner-city riots at Brixton and Toxteth but elsewhere too, Derek Hatton in Liverpool, Ken Livingstone at the GLC, David Blunkett’s Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire, the 1984-85 Miners strike, followed by the weekly night-time siege of the new Rupert Murdoch HQ at Wapping. There was an ongoing mainland IRA campaign with the Brighton Grand Hotel Bombing in 1986 arguably its most breathtaking operation of all. In 2009 the New Statesmanpublished a special edition to mark the 30th anniversary of 1989 which it dubbed ‘The Year of the Crowd.’ It ranged over the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square Massacre and the frenzy in Tehran amongst the huge numbers turning out for the Ayatollah’s funeral.

England? Hillsborough, just another Liverpool FA Cup semi-final but a day that ended with fans dying simply because they wanted to watch their team. Andrew Hussey contributed the Hillsborough essay in which he makes the following key point to describe the images and memories of Liverpool’s Kop and the fans who stood and sang their hearts out for their team:

“This was the mob, the crowd, the working class in a group and in action, but it was nothing to be feared. The humour and dignity of this crowd were iconic. These images announced to the world the cultural vibrancy of ordinary people and their pleasures. To this extent, Liverpool fans were as crucial a component of 1960s pop culture as the Beatles.”

Of course as everyone knows the Beatles were bigger than God. But that depth of warm appreciation had been hollowed out by the harsher climate of the 1980s as Hussey succinctly explains :

“ By the end of the Thatcherite 1980s this same crowd had become the object of scorn and derision. To be working class, to be a football fan, to be unemployed and northern was to be scum.”

And 96 died.

During the 1980s fans’ behaviour was met with legislative and media mood swings between the uselessness of platitudes and inertia to moral panic and the clamour for the punitive. Those who were in a position to do something ended up doing nothing. The worsening conditions at grounds just got worse, the policing not much better, crowd safety measures close to non-existent, the rising tide of racism looked away from in the hope that it might go away, or not even caring if it did or didn’t. To go to football at least for some was to know something was seriously wrong.

This is an edited extract from Mark Perryman’s new book 1966 and Not All That, published by Repeater Books in mid-May available pre-publication from here.

England Always Dreaming

23.04.16

Author of a new book on ’66 Mark Perryman explores for St George’s Day the connections between English football’s golden moment and national identity

In CLR James’ magnificent book on Caribbean cricket Beyond a Boundary he criticises both liberal and socialist historians of 19th century England who can write books on the period entirely missing out any mention of the most famous Englishman of the era, cricketer WG Grace. Recently I was reminded of this by a spate of articles seeking to remind the Left that it ignores at its peril The English Question.

In CLR James’ magnificent book on Caribbean cricket Beyond a Boundary he criticises both liberal and socialist historians of 19th century England who can write books on the period entirely missing out any mention of the most famous Englishman of the era, cricketer WG Grace. Recently I was reminded of this by a spate of articles seeking to remind the Left that it ignores at its peril The English Question.

David Marquand manages to write a New Statesman essay on the subject without mentioning the most salient and obvious expression of Englishness at all, not once. Timothy Garton-Ash writes a similar piece for the Guardian choosing to ignore this most obvious of expression of Englishness too, though to be fair he does give rugby a passing mention. I am of course referring to football, a subject the political class wears as a badge of faux-authenticity without actually having the merest grasp of its meaning for a debate they now hold so dear.

My home town is Lewes in East Sussex. Home of Tom Paine, the Bloomsbury Group and Bonfire, you don’t get much more traditionally English than this. Yet despite a spot of Saturday morning Morris Dancing outside The Volunteer St George’s Day will pass by scarcely noticed (it’s today in case you haven’t).

This St George’s Day is a tad special for those of a literary persuasion as it also marks Shakespeare’s 400th anniversary. I’m not one for cultural relativism, I’ve as much time for the Bard as most but the most influential piece of writing in the English language isn’t Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet or Midsummer Night’s Dream. Instead it’s a book written by committee in a room above a pub, The Freemason’s Arms in Covent Garden. On 26th October 1863 the thirteen laws of football were codified in a single rulebook and adopted at the meeting that founded the world’s first Football Association.