A Games That Belonged To The People

05.08.2016

Mark Perryman of Philosophy Football uncovers the hidden history of Barcelona ‘36

When the Rio Olympics begin tonight beyond the glitz and the glamour of the opening ceremony spectacle there will be popular protests right across the city. It was the same at London 2012 and the Vancouver Winter Games of 2010. Throughout the build up to both Sochi 2014 and Beijing 2008 there were global protest to force attention on LGBT discrimination and human rights issues in host countries Russia and China. But of course once the gold medal rush began the protests and concerns were almost universally marginalised. I suspect it will be more or less the same with Rio.

How do we manage both to enjoy and celebrate sport while maintaining some basic principles of equality and solidarity? Perhaps what we need is a political culture that takes sport seriously – what we do with Philosophy Football mixing sport and culture is one brave and audacious attempt to do precisely that – rather than treating it simply as a suitable add on for photo opportunities and celebrity endorsements of this issue or that.

For an idea of what might be possible a useful starting point would be to revisit the 1930s. This was of course the era of the rise of Mussolini and Hitler. Mussolini put great emphasis on football as the means of portraying his idealised fascist nation, Italy hosted and won the 1934 World Cup and retained the trophy four years later too at France ’38 on the eve of war. But it is Hitler’s Berlin Olympics of 1936 which are most widely remembered for the clash of political ideology and sporting spectacle. The four gold medals won by black American sprinter and long jumper Jesse Owens of course have come to symbolise the way sport can subvert an intended political message to devastating effect. But what scarcely gets mentioned is the widespread efforts of both the International Olympic Committee to make a positive case for the Nazi regime to host the Games in order to head off calls to boycott Berlin.Much of this lobbying was done by notorious anti-semite Avery Brundage who went on to become the President of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. This is the history the Olympic movement would prefer remained hidden.

But the 1930s was also the era of the Popular Front. A political culture that extended way beyond traditional definitions of activism. Inspired by both the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rising threat of fascism the Popular Front embraced literature – the Left Book Club – poetry, art, perhaps most famously Picasso and Miro, music – including Benjamin Britten, the festive and the celebratory as well as the militancy of street protests, notably in 1936,Cable Street. And sport played its part too.

But the 1930s was also the era of the Popular Front. A political culture that extended way beyond traditional definitions of activism. Inspired by both the example of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rising threat of fascism the Popular Front embraced literature – the Left Book Club – poetry, art, perhaps most famously Picasso and Miro, music – including Benjamin Britten, the festive and the celebratory as well as the militancy of street protests, notably in 1936,Cable Street. And sport played its part too.

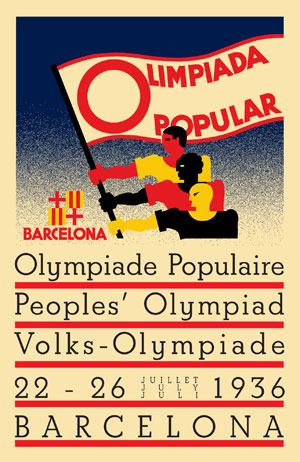

The Spanish Republican government took a political decision to boycott the Berlin Games. They correctly judged that with the Olympic movement barely interested in putting up any opposition Berlin would become a platform for Hitler and Goebbels to sanitise and propagandise for Nazism. Jesse Owens notwithstanding, they were proved absolutely correct. However this was no ordinary boycott. The Spanish government pledged to host a People’s Olympiad in the Republican stronghold of Barcelona with over 6,000 athletes from across the world taking part. Timed to take open just a few weeks before Berlin this would have been a powerful example in practice of a sporting internationalism vs the racialisation of sporting endeavour the Nazis were seeking to promote. Then, on the eve of the opening ceremony, Franco launched his murderous assault on the Spanish Republic, the country was plunged into civil war and the Games cancelled. Most athletes were forced to leave though some chose to stay and join the International Brigades in their fight for Spain’s land and freedom.

The point about Barcelona ’36 is that it didn’t happen in isolation. Other ‘alternative’ Games included Czechoslovakia’s 1924 National Gymnastics Festival organised by the Workers Gymnastics and Sports Association, the first Workers’ Olympics in Frankfurt 1925, Moscow’s Spartakiad of 1928, the Vienna Workers’ Olympics of 1931, a second Spartakiad of 1933 organised by the Red Sport International, the third and final Workers’ Olympics, Antwerp 1937. And there were alternative Women’s Olympics too, four in all 1922 Paris, 1926 Gothenburg, 1930 Prague and 1934 London.

It’s almost impossible to imagine anything of this scale of imagination and purpose today. Jules Boykoff in his brilliant new political history of the Olympics, Power Games, has a novel explanation of why such an alternative model of sport is so important rather being being simply, if necessarily, against this and that. He describes the Olympics, and other global sporting spectacles such as football’s World Cup, as ‘celebration capitalism’ juxtaposing this to Naomi Klein’s theorisation of ‘disaster capitalism’. For the duration of Rio we will be treated over and over again to the Olympian maxims of inspiration, regeneration and participation. Huge public and material investment in infrastructure and Gold Medal-winning performances to celebrate what, and benefit whom? To state this is to engage with a popular common sense,, not to moan and whinge about what Rio 2016 or London 2012 fail to achieve but to be inspired by Barcelona ’36 to shape a better sporting culture for all.

Philosophy Football’s Barcelona ’36 T-shirt is available from here