Battle of Britons

15.06.2016

Mark Perryman previews England v Wales as competing versions of nationhood

The traditional ‘Battle of Britain’ match is of course England v Scotland, the very first recognised international football match dating back to 1872 and the most intense of rivalries ever since. The last time two ‘home’ nations met in a major tournament it was again England v Scotland at Euro 96. The spark in so many ways for the break-up-Britain agenda that was to follow the Blair government devolution referendums a year later and latterly transformed into the SNP ‘tartan landslide’. Once derided by Jim Sillars as ‘ninety-minute nationalists’ Scots today are so busy building a nation they can call their own they haven’t much time left over for their under-performing football team, ouch!

Instead it will be the Welsh who will take the field on Thursday against Scotland’s ‘auld enemy’. An encounter inevitably affected by the ugly scenes the weekend before in Marseille. It was the historian Eric Hobsbawm who once observed, “ The individual, even the one who only cheers, becomes a symbol of the nation himself.” This was sadly true of those brutalised encounters in the south of France. Though as my friend Julie Nerney who was there has pointed out the habit of most travelling England fans is to “learn where to go and not to when you travel to games. Avoiding the places where it was obvious there was a chance of things kicking off. Knowing what the signs of a flashpoint were and extricating yourself from any situation where you might simply end up in the wrong place at the wrong time.” And thus in Marseille as Julie reports “Bars in the main square of any town are a magnet for trouble. Many sensible fans give them a wide berth.” This is the hidden story behind the headlines about an episode like Marseille 2016. Meanwhile in another part of town I’d helped organise a fans’ mini tournament England v Russia, another mate, John Lunt, who played describes the experience, “Had fun, we may have lost all our games, but made a few friends when others were doing their best not to.”

Instead it will be the Welsh who will take the field on Thursday against Scotland’s ‘auld enemy’. An encounter inevitably affected by the ugly scenes the weekend before in Marseille. It was the historian Eric Hobsbawm who once observed, “ The individual, even the one who only cheers, becomes a symbol of the nation himself.” This was sadly true of those brutalised encounters in the south of France. Though as my friend Julie Nerney who was there has pointed out the habit of most travelling England fans is to “learn where to go and not to when you travel to games. Avoiding the places where it was obvious there was a chance of things kicking off. Knowing what the signs of a flashpoint were and extricating yourself from any situation where you might simply end up in the wrong place at the wrong time.” And thus in Marseille as Julie reports “Bars in the main square of any town are a magnet for trouble. Many sensible fans give them a wide berth.” This is the hidden story behind the headlines about an episode like Marseille 2016. Meanwhile in another part of town I’d helped organise a fans’ mini tournament England v Russia, another mate, John Lunt, who played describes the experience, “Had fun, we may have lost all our games, but made a few friends when others were doing their best not to.”

Little of this features in how most would think of the Englishness on parade at Euro 2016. Britain is a mix of contradictions, at home right now. Bathing in the collective and transnational experience of being European via the Euros while according to the referendum polls more than half the country couldn’t exit the continent fast enough For the English such contradictions are exacerbated by a very particular identity crisis. When England and Wales line-up for kick off each set of players, and fans will belt out their respective National Anthems. The Welsh, Land of our Fathers, while the English, like the Northern Irish, have to sing somebody else’s. Eh? That’s right us and the Northern Irish don’t have an anthem as every other country does, instead we have to sing an anthem that belongs to somewhere else, Great Britain. Yet the English tenaciously cling to an anthem which isn’t even ours as a source of great comfort. “Long to Reign Over Us, Happy and Glorious ” in those two lines the English contradictions of subjecthood neatly summed up.

American author Franklin Foer in his book How Soccer Explains the World points to the range of forces of globalisation which threaten this settled subjecthood founded on an unchanging notion of what it means to be English. Take a look at the players on any Premier League pitch, in the technical area the managers, coaches and backroom staff, the ownership of the bigger, and some smaller, clubs, the audience in the stands and via TV, the exchange of playing styles and tactics. There is very little left about our football which is precisely English.

Despite these forces of Europeanisation and globalisation however Foer makes a key point about soccer(sic) and culture; “ Of course, soccer isn’t the same as Bach or Buddhism. But it is often more deeply felt than religion, and just as much a part of the community’s fabric, a repository of traditions.” This is why England v Wales is always going to be about more than a football match.

An Englishness subject to imperial and martial tradition helps explain the ugly saliency of immigration as an issue in the Euro referendum non-debate and this reminds me of Satnam Virdee’s description of 1970s Powellism.

A powerful re-imagining of the English nation after empire, reminding his audience it was a nation for whites only. In that historical moment the confident racism that had accompanied the high imperial moment mutated into a defensive racism, a racism of the vanquished who no longer wanted to dominate but to physically expel the racialised other from the shared space they occupied, and thereby erase them and the Empire from its collective memory.

The make-up of the England team might appear a powerful antidote to these forces of reaction. But unlike the Welsh, and most particularly the Scots, the English barely possess a civic understanding of nationhood, instead it is mired in the racial. A football team may project some kind of alternative sense of being English but in the absence of political forces to make that argument it’s not enough. In June 2016 that couldn’t be more obvious.

None of this will help us predict the score when Bale’s Welshmen take on Rooney’s Englishmen but it certainly helps us understand how such an encounter is framed, consumed and understood. Performance isn’t something restricted just to the pitch y’know.

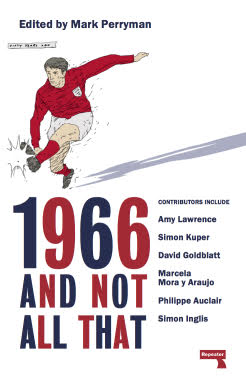

Mark Perryman is the editor of the new book 1966 and Not All That published by Repeater Books and available from Philosophy Football